The placid veneer of recent inflation statistics belies the Multiflationary tensions that persist just beneath the surface. While headline price growth has appeared relatively stable over the past two years—albeit at dramatically elevated levels following the COVID disruption and policy response—the underlying forces driving Multiflation have not abated—if anything, they are gathering strength.

Twitter/X: @bewaterltd. Suggestions? Feedback.

Not investment advice. For educational/informational purposes only. See Disclaimer.

Contents

Inflation: Mounting Evidence From Business Surveys

Inflation: Mounting Evidence From Earnings Season

Money Illusion And Earnings “Growth”

Macro Stats: Cooking The Books At The Ministry Of Plenty

Troubling Scenarios For Multiflation’s Next Path

Inflation Rising?

For the past two to three years, headline inflation growth has remained relatively subdued—albeit at dramatically higher price levels reached as a consequence of the unprecedented COVID monetary response and supply chain disruptions.

This plateau effect has fostered dangerous complacency. While economists and policymakers debate inflation metrics and the potential impact of tariffs, the businesses actually producing goods and services are preparing for significantly higher prices. Business surveys and corporate earnings reports reveal mounting cost pressures that have yet to register in official statistics.

Inflation: Mounting Evidence From Business Surveys

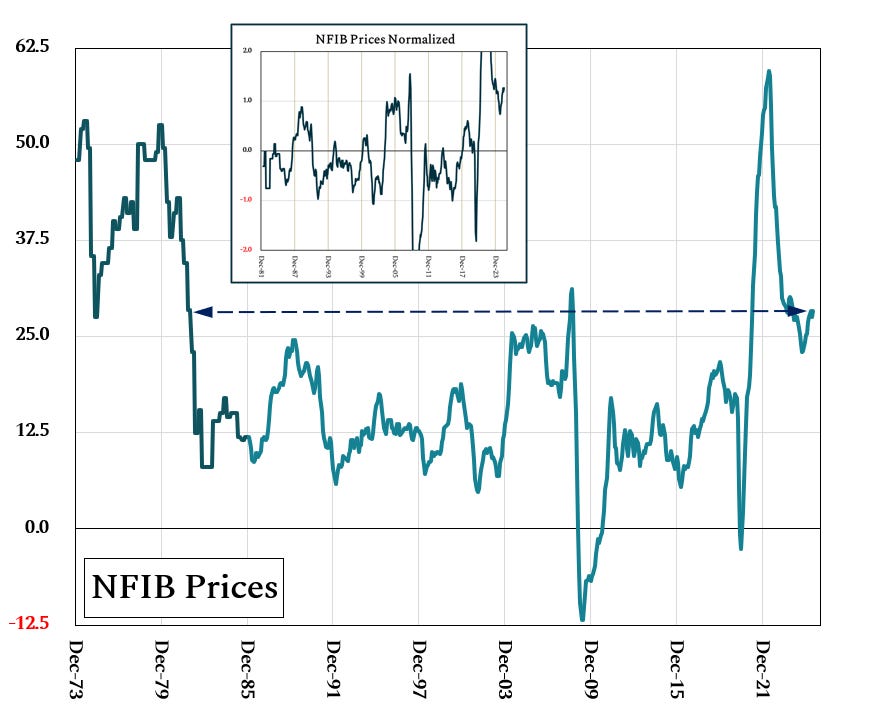

Excluding the COVID-19 anomaly, the National Federation of Independent Business (NFIB) Small Business price component has reached levels seen only once over the past four and a half decades; the sole comparable period being the pre-2008 commodity boom during which oil prices soared to nearly $150 per barrel. This metric has been climbing almost without interruption for nine consecutive months, suggesting that small businesses are experiencing persistent and intensifying cost pressures.

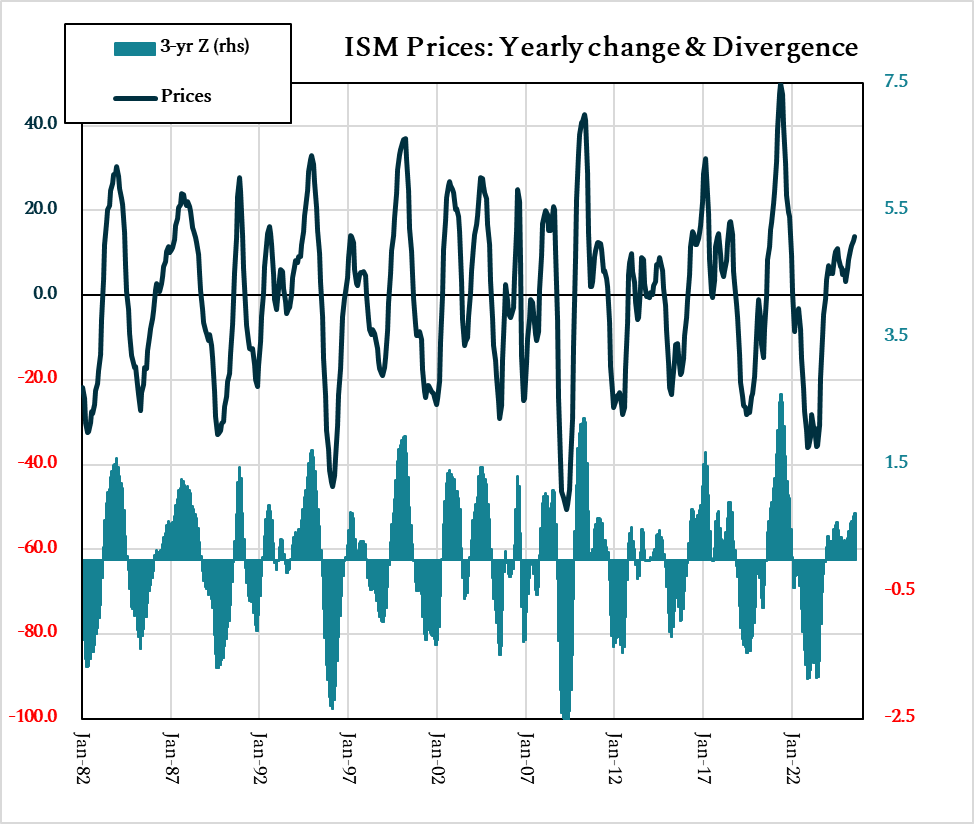

While not quite as dramatic as the NFIB data, the Institute for Supply Management (ISM) Manufacturing index tells a similar story, reaching seven-year highs and rising almost continuously since last autumn:

The increase in the ISM price component over the past twelve months is the greatest since the COVID lockdown disruptions. Excluding COVID, the last comparable surge occurred in summer 2018—a period during which Treasuries hit a 7-year high and stock markets fell 20-25%.

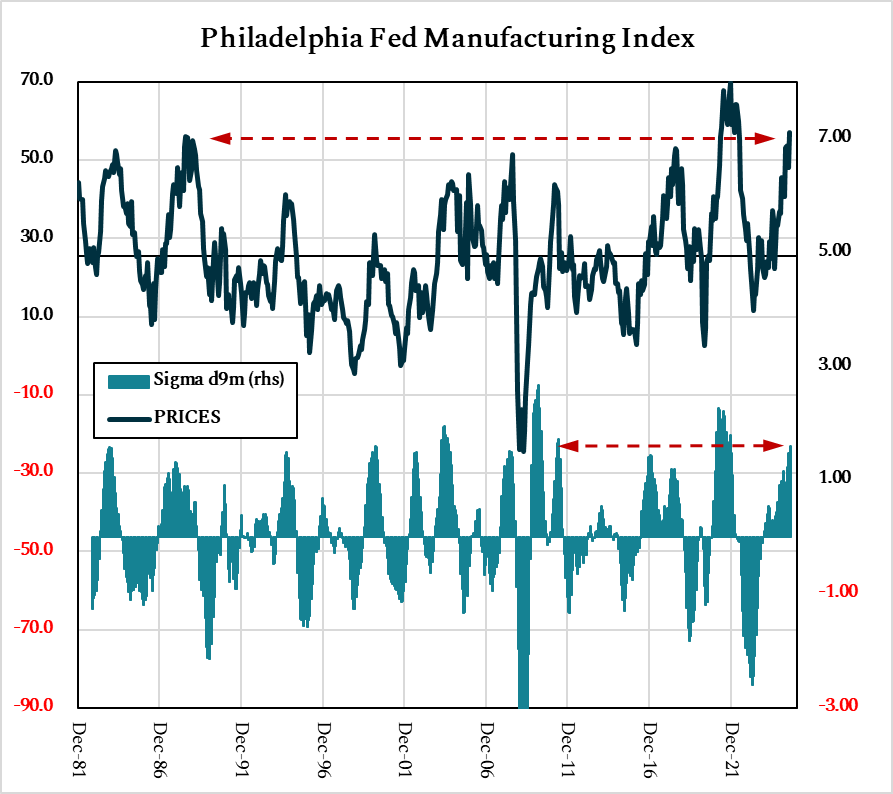

The Philadelphia Fed Manufacturing Index, a generally more erratic indicator but one with a well-established history, offers substantial corroboration of these trends:

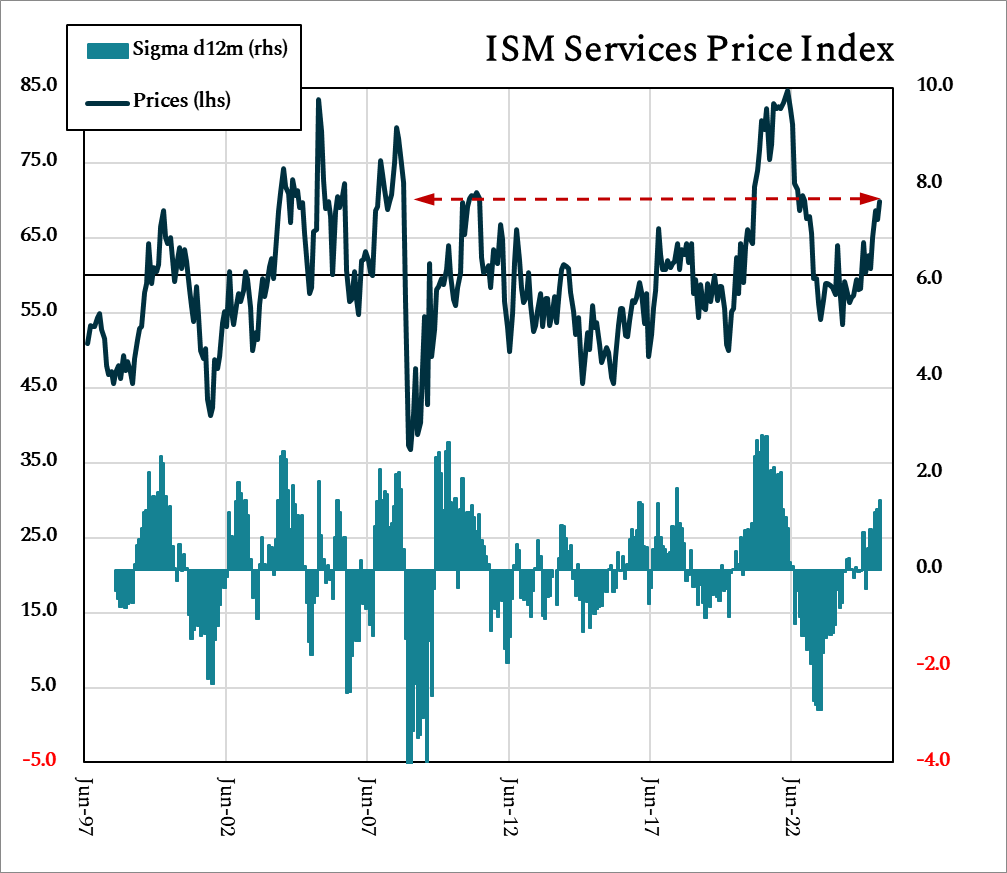

Even the service sector, which had remained relatively insulated from these pressures (again, outside of COVID), is experiencing or expecting higher pricing; surveys now show price inflation expectations at close to the highest levels since the Financial Crisis in 2008:

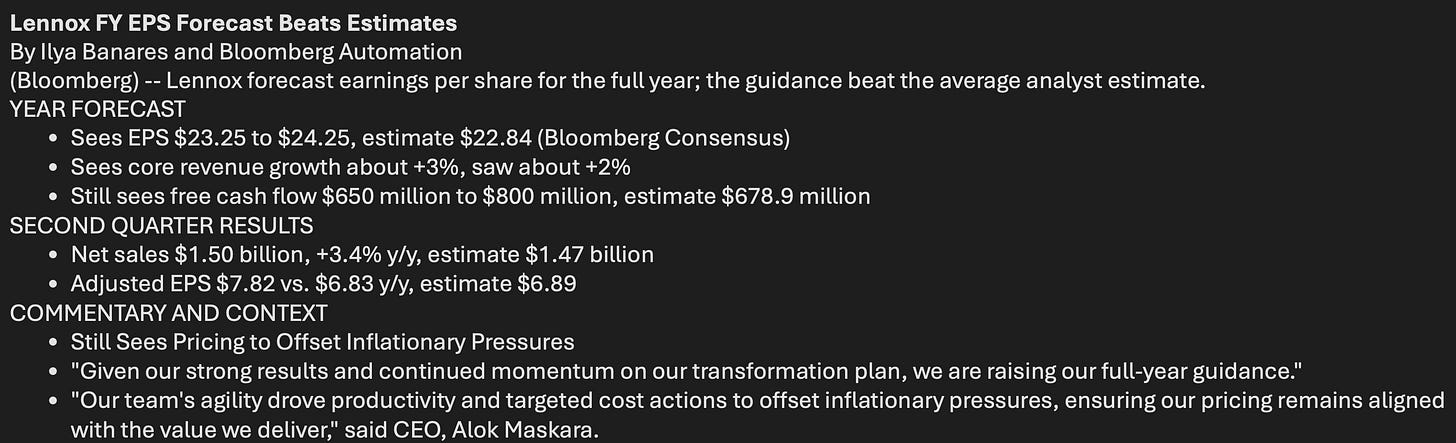

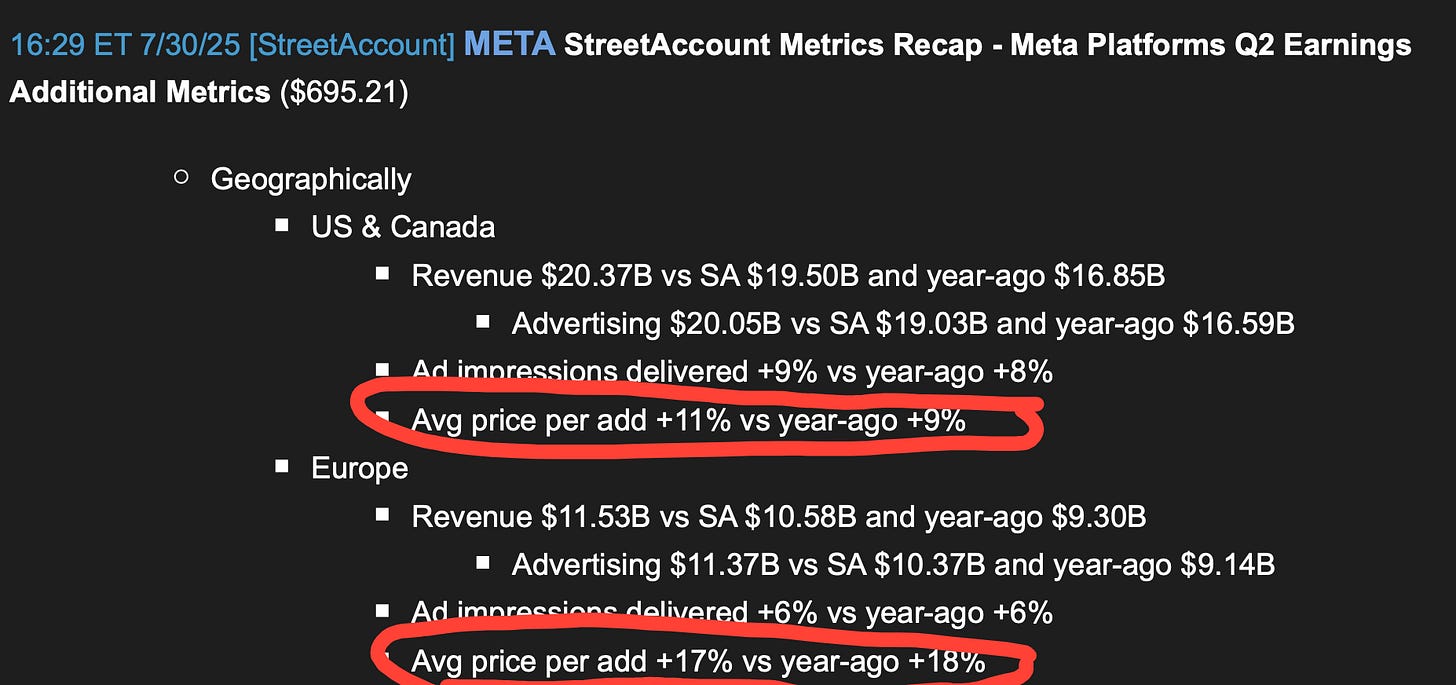

Inflation: Mounting Evidence From Earnings Season

The mounting cost pressures evident in business surveys are beginning to manifest in corporate earnings reports. While tariffs certainly account for some of these pressures, they also often serve as convenient cover for rising prices, and companies appear to be facing broad-based cost increases that extend well beyond trade policy.

Japanese automakers are perhaps illustrative of part of the delayed tariff impact. They generally avoided raising prices during the tariff disputes while under pressure from the Trump administration. Once deals were struck, the deferred price increases materialized; similar developments appear to be emerging across other industries.

Money Illusion And Earnings “Growth”

One particularly pernicious aspect of Multiflation is “money illusion”. Money illusion is a behavioral bias that occurs when people are fooled by bigger dollar amounts without realizing that those dollars don't buy as much as they used to.

Multiflation and money illusion have rendered our economic measurement systems poor guides to reality. Corporate earnings reports, for example, increasingly reflect “money illusion” rather than genuine indicators of underlying business performance. As money loses purchasing power and becomes an unreliable measuring stick, companies and economies may report seemingly impressive growth figures that obscure stagnant or declining real business activity—even as the underlying monetary disorder undermines economic coordination and produces mounting economic dislocations. This disconnect between reported financial performance and actual business fundamentals misleads entrepreneurs, investors, and policymakers into drawing false conclusions about economic health based on inflated dollar figures rather than real economic growth.

As we wrote in the original Sorcerer’s Apprentice in January 2021:

Perhaps the most important conclusion is that we must inculcate a “Multiflation mindset”—meaning that we no longer think of prices purely relative to fiat currencies. Trying to coordinate a society without a stable ledger for value is akin to trying to build a house with a yardstick that varies in length every day. Some days you come in to work and the yardstick is 20”, other days it’s 45”, still other days 62.5”, and so forth. Calculation becomes impossible: the result will be a totally dysfunctional house that has no utility. The same is true for society as well: without stable money there can be no economic calculation or coordination.

This Multiflationary confusion is playing out across corporate America right now. Consider an illustrative example: a company announces that its earnings jumped 18% compared to last year. That sounds impressive—until you analyze how they achieved that growth.

The company only sold 3% more goods than the prior year, but it raised prices on its products, which boosted revenue by 6%. Another 6% of the growth came from spreading those higher revenues across the same fixed costs. Another 3% came from buying back company stock, which makes earnings per share look better simply because there are fewer shares to divide the profits among.

Strip away the noise, and the company sold only 3% more products than last year while presenting itself as a growth success story. Investors see the 18% earnings growth and assume the business is thriving, but the reality is far less impressive.

This pattern has become widespread across corporate earnings, creating a dangerous disconnect between appearance and reality. If companies can barely manage tepid earnings growth even with the benefit of nominal price increases and financial engineering working in their favor, their core businesses are likely in worse shape than analysts realize.

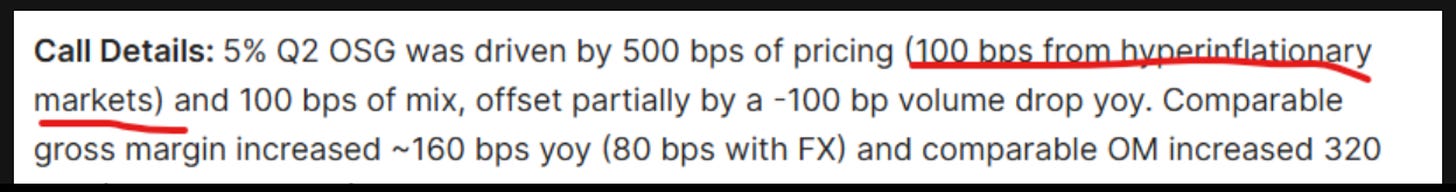

For example, one sellside bank report on Coca Cola’s earnings noted a volume drop offset by “hyperinflationary markets” pricing:

Institutional Rot

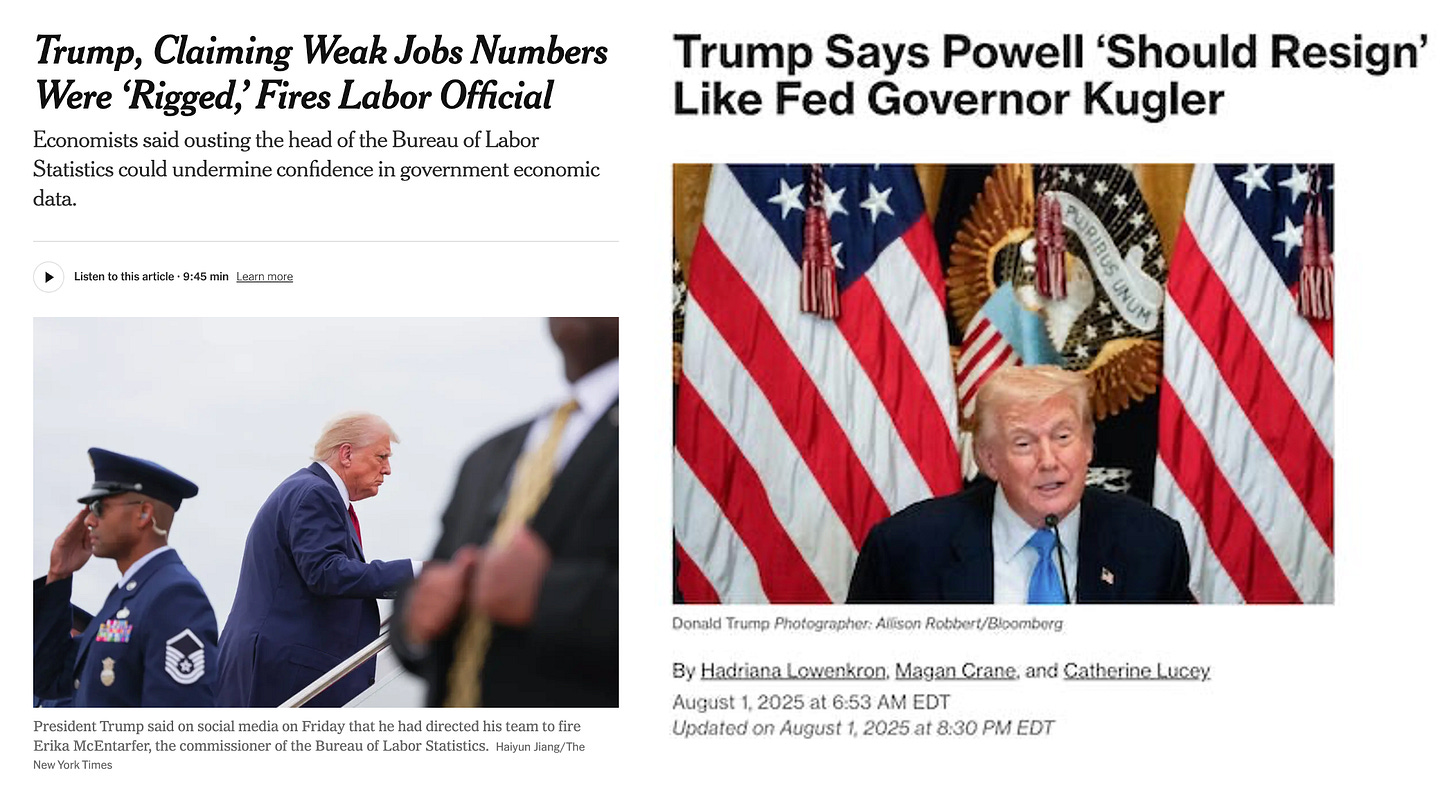

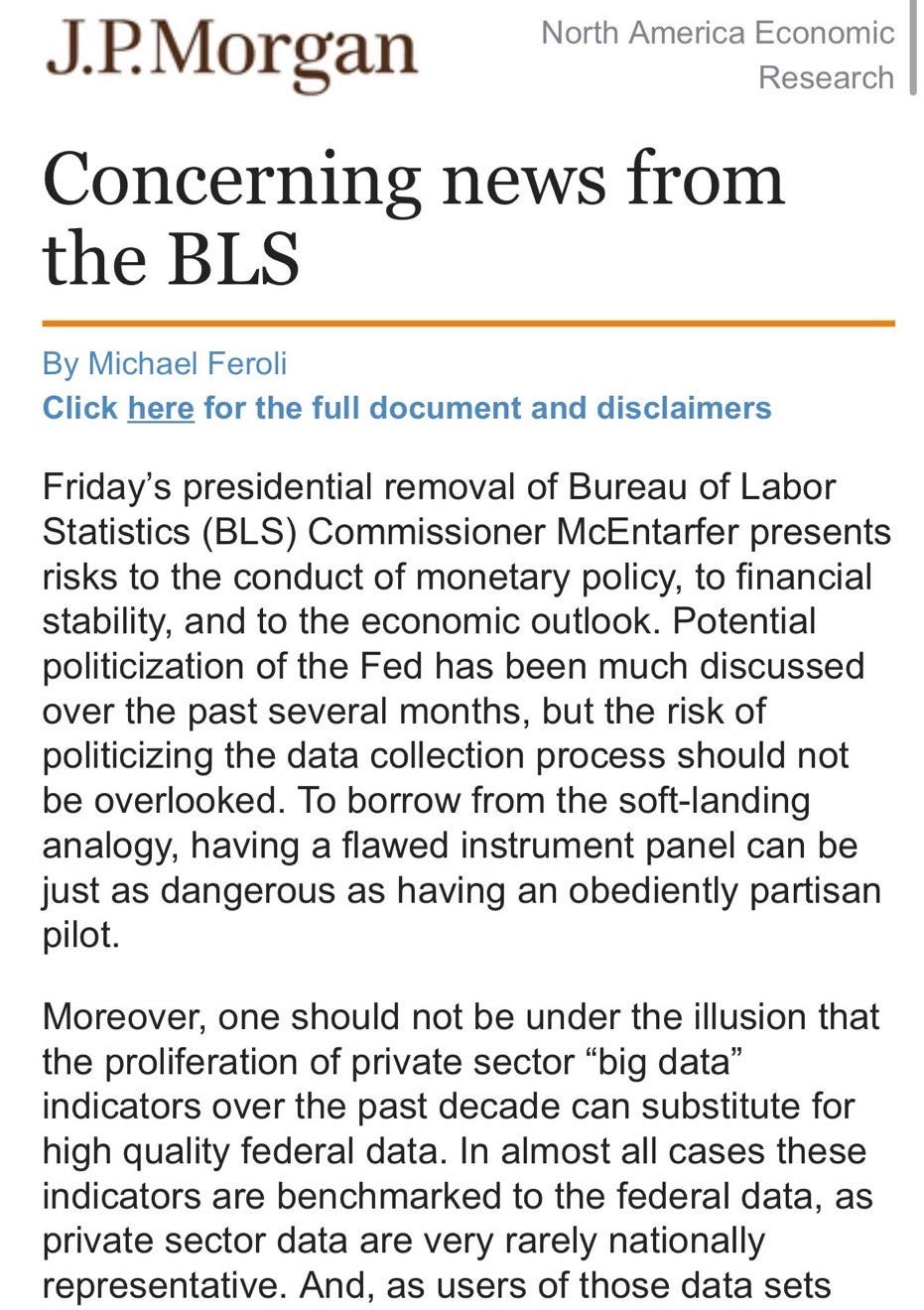

The accuracy and politicization of macro statistics were front page headlines this week:

The recent resignation of Fed Governor Kugler and President Trump’s dismissal of the Bureau of Labor Statistics head over allegedly “rigged” employment data reflects a broader erosion of institutional credibility that extends far beyond any single administration or data series (sidenote: the BLS is also responsible for producing the CPI statistics).

Even setting aside questions of political interference and accuracy, these developments should prompt skepticism about the usefulness of even honest aggregate economic statistics; these overly-broad macroeconomic “blobs” inherently obscure the complex reality experienced by businesses and consumers, as discussed in Coding The Financial Matrix.

Macro Stats: Cooking The Books At The Ministry Of Plenty

As we wrote last year in The Vibes Economy: Coding The Financial Matrix (link here for the full piece):

The use of aggregate economic statistics has…opened the door to deliberate manipulation of these figures for political purposes. As these abstract numbers have gained primacy in shaping policy and public perception, the temptation to alter them for political gain has proven irresistible. This potential for statistical sleight-of-hand brings to mind a chilling parallel from Orwell’s discussion of the Ministry of Plenty in 1984.

Ostensibly responsible for Oceania’s command economy, MiniPlenty controls the rationing of food, supplies, and goods. However, its true purpose is far more insidious. The Ministry perpetually issues false economic reports, such as claims of increased economic production, even as actual output declines. This deliberate deception maintains the illusion of prosperity and progress, keeping the populace ignorant of their true economic conditions. By manipulating these economic figures, the Party ensures that the citizens remain poor and misinformed, making them easier to control:

But actually, he thought as he re-adjusted the Ministry of Plenty’s figures, it was not even forgery. It was merely the substitution of one piece of nonsense for another. Most of the material that you were dealing with had no connexion with anything in the real world, not even the kind of connexion that is contained in a direct lie. Statistics were just as much a fantasy in their original version as in their rectified version. A great deal of the time you were expected to make them up out of your head. For example, the Ministry of Plenty’s forecast had estimated the output of boots for the quarter at 145 million pairs. The actual output was given as sixty-two millions. Winston, however, in rewriting the forecast, marked the figure down to fifty-seven millions, so as to allow for the usual claim that the quota had been overfulfilled. In any case, sixty-two millions was no nearer the truth than fifty-seven millions, or than 145 millions. Very likely no boots had been produced at all. Likelier still, nobody knew how many had been produced, much less cared. All one knew was that every quarter astronomical numbers of boots were produced on paper, while perhaps half the population of Oceania went barefoot. And so it was with every class of recorded fact, great or small. Everything faded away into a shadow-world in which, finally, even the date of the year had become uncertain.

Echoes of such manipulation resonate in our own world. From creative accounting in GDP calculations to redefining measures of inflation or unemployment, statistical sleight of hand has become a powerful tool for painting a rosier picture of economic performance. These manipulations further divorce our economic discourse from reality, creating a statistical mirage that often bears little resemblance to the economic conditions experienced by ordinary citizens.

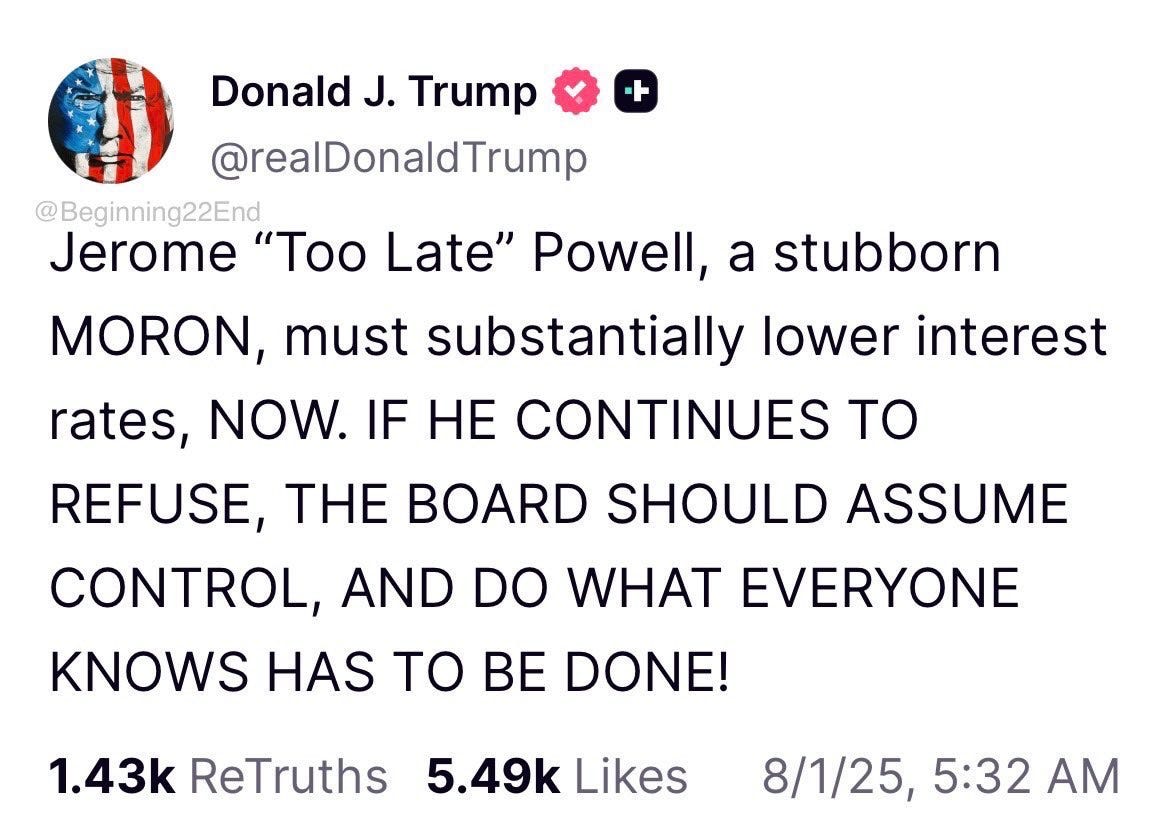

Pressure On The Fed

Pressure on the Fed to cut rates is rising; Wall Street is now pricing in three Fed rate cuts by the end of the year.

Potentially more troubling is that the recent upheaval in key economic institutions—from the dismissal of data collection bureaucrats to the resignation of a Fed Governor to the increasingly strident calls for a new Fed Chair and interest rate cuts—may signal an erosion of the institutional foundations that underpin monetary and political credibility.

Regardless of one's politics, this pattern of institutional instability has historically served as a precursor to periods of accelerated currency debasement; markets tend to respond to such institutional decay by anticipating higher inflation and reduced policy credibility.

A few weeks ago, even former Fed chairs Ben “Helicopter” Bernanke and Janet “Tamagotchi” Yellen penned an opinion piece for the New York Times, arguing that “A particularly clear lesson of history is that when central banks are forced to finance government deficits—by keeping interest rates excessively low, to cite one possibility—the result is inevitably higher inflation and economic damage.”

Troubling Scenarios For Multiflation’s Next Path

The current evidence suggests we stand at a critical juncture. While credit markets attempt to purge some of their post-COVID excesses, the mounting cost pressures revealed in business surveys and corporate earnings, the money illusion distorting economic growth metrics, and the institutional upheaval undermining policy credibility all point toward the same unsettling conclusion: Multiflation has not been conquered but merely temporarily obscured. Further rate cuts may have unintended consequences.

The most likely scenarios based on our current economic trajectory:

Scenario One: Inflation Reemergence

The current cost pressures overwhelm companies' ability to absorb them, leading to a wave of price increases across multiple sectors. The recent plateau in headline inflation proves temporary as businesses finally capitulate to rising input costs.

The Federal Reserve would face a difficult choice: raise interest rates into what might already be slowing economic growth to re-anchor inflation and inflation expectations, or risk further eroding its credibility by allowing inflation to accelerate. Either path could prove destabilizing.

Scenario Two: The Stagflationary Trap

This presents a potentially more pernicious outcome where rising costs coincide with weakening demand. Companies facing higher input prices discover they cannot fully pass these costs through to increasingly price-sensitive consumers. This leads to margin compression, reduced business investment, and employment pressures—even as prices for essential goods and services continue rising.

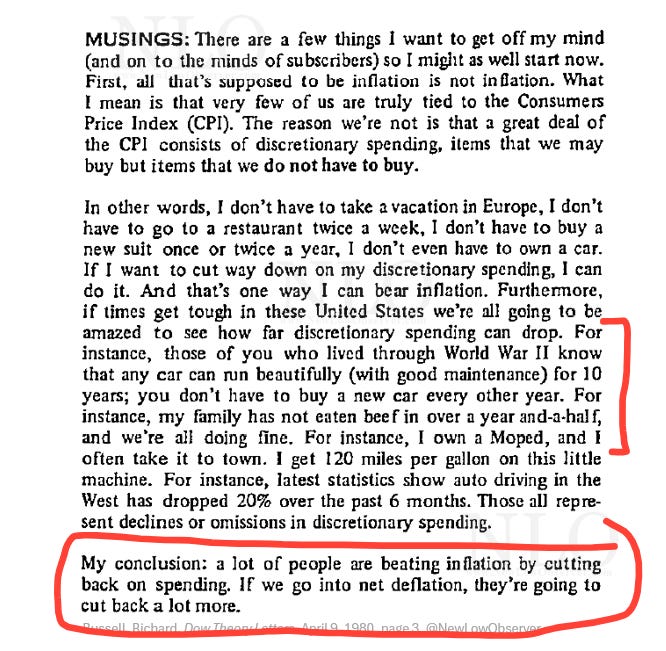

The result would be persistently elevated prices for necessities combined with economic stagnation—a combination that historically proves both economically destructive and politically volatile.As New Low Observer posted today from Richard Russell’s April 9 1980 letter, written during the last stagflation:

Both scenarios represent the natural consequence of attempting to coordinate a complex economy using an increasingly unreliable monetary measuring stick, creating the very economic dislocations that stable money was designed to prevent. Whether we experience a resurgence in broad inflation metrics, the stagflationary one-two punch of rising prices and economic recession, or some other manifestation of Multiflation, the disorder ultimately stems from the same fundamental problem: the breakdown of money's function as described in Money’s Metamorphosis (link here).

This contradictory dynamic of deflationary credit pressures colliding with inflationary cost pressures and the undermining of institutional credibility creates particularly treacherous conditions for policymakers and offers no easy policy solution; cutting interest rates into potentially accelerating inflation could amplify rather than resolve the building monetary disorder and economic dislocations, while maintaining or raising rates to combat incipient inflation could further weaken an already fragile economy.

Whether the economy experiences a resurgence of inflation or a more damaging combination of high prices and weak revenues will likely depend on how policy uncertainties resolve and whether revenue and productivity growth and can keep pace with rising costs.

Get gold an silver coins and hide them NOW as super-hyper-stagflation hits — that is, a scenario with extremely high inflation**, **economic stagnation**, and possibly **rising unemployment — most traditional investments don't do well. However, some assets historically hold or gain value in these extreme conditions.