The Vibes Economy: Coding The Financial Matrix

The Keynesian Kaleidscope Part III

New to the series? Start with our foundational posts on Hyperreality and the Financial Matrix for essential context, or explore the full Table Of Contents.

Part of the Sorcerer’s Apprentice series, originally published privately on January 13, 2021. Updated, revised and expanded for public release on August 26, 2024, with previously omitted content restored for completeness, edits to improve readability, and enhanced graphics.

The Keynesian Kaleidoscope sub-series examines how modern economic thought has fundamentally reshaped our reality. Just as money’s metamorphosis increasingly divorced it from physical reality, Keynes detached economics from the real world it was intended to represent.

In Part I, we explored how Keynes inverted the relationship between the “real economy” and its monetary shadow, elevating abstract symbols over tangible economic activity. Part II revealed how Keynesian economics and the “economy-as-car” meme transformed our perception of the economy into a system that could be engineered by “Economist-Kings”.

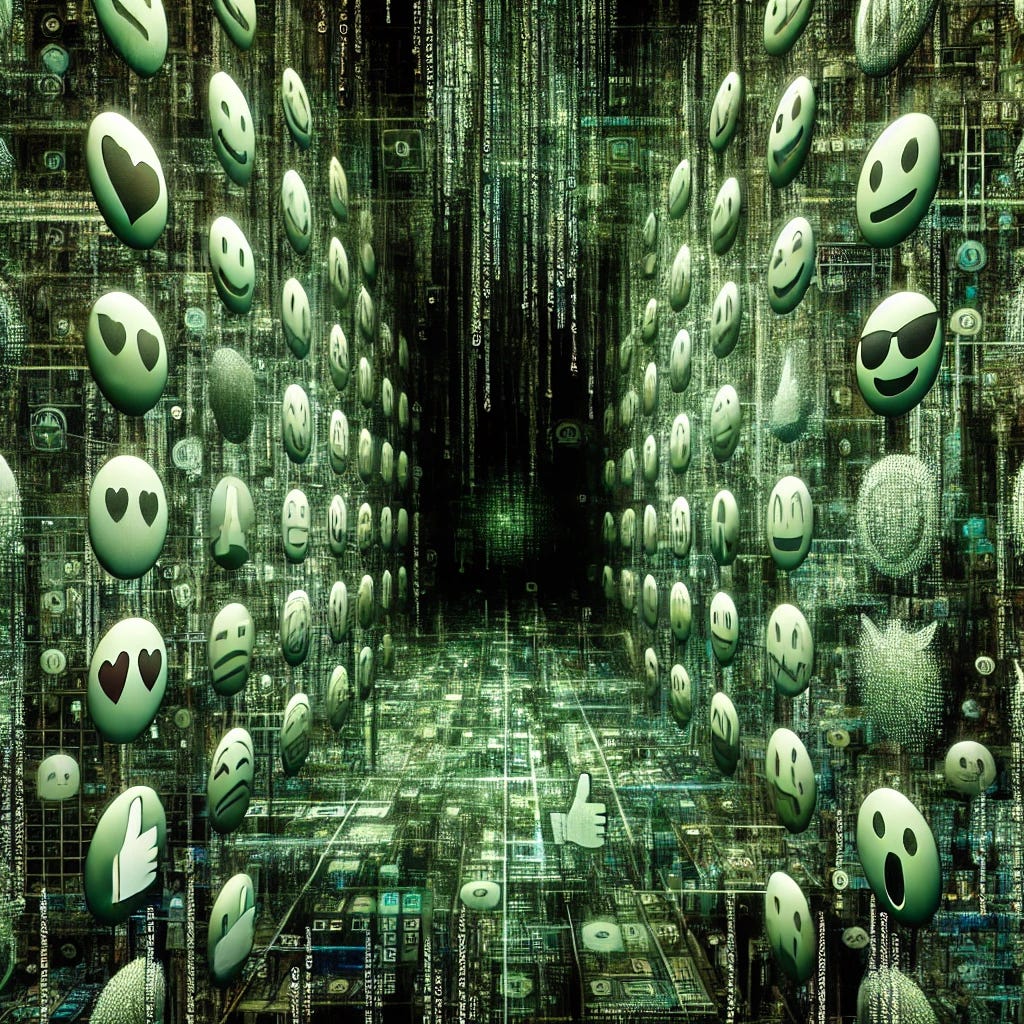

This final installment synthesizes these concepts, illuminating how the Keynesian Revolution has fostered a hyperreal “Vibes Economy” where collective sentiment and memes increasingly drive economic outcomes. We further explore how modern economics underpin the Financial Matrix—a self-referential system that has transformed policy, markets, and our understanding of economic “fundamentals.”

N.B.: Keynes and Keynesian economics are used herein as convenient—albeit not entirely accurate—shorthand for “modern” economics more broadly.

Ten Milestones On The Road To Hyperreality

1. The Metamorphosis Of Money

2. Keynes' Kaleidoscope <== YOU ARE HERE

3. Central Banks’ Money Printer Go BRRRR

4. Silicon Shadows: The Digital Detachment Of Economics & Finance 5. The Institutionalization Of Finance

6. The Rise of Skynet: The Algorithmization Of Finance

7. The Symbolic Alchemy Of Risk

8. “We’re All Quants Now”

9. Social Media & “The Ecstasy Of Communication”

10. The Consumerification of FinanceUnder the spell of powerful optical illusions we have become accustomed to viewing man as a grain of sand next to his machines and apparatuses. But the apparatuses are, and will always be, no more than a stage set for a low-grade imagination…Man has immersed himself too deeply in the constructions, he has devalued himself and lost contact with the ground.

—The Forest Passage, Ernst Junger

How Economics Retreated Back Into Plato’s Cave: Inversion Of Means & Ends

Prior to the Keynesian Revolution, the “real economy” held center stage for economists, and money was cast as its symbolic “shadow”— a critical but primarily passive reflection and transmitter of true economic activity. The focus was predominantly on what is now called microeconomics: tangible goods, services, and the entrepreneurs who produced them—as well as the actions and interactions of countless individuals—as the core of the “real economy.” Supply (production) acts as the driver; demand naturally follows supply.

Keynes upended this worldview, inverting the relationship between the “real economy” and its monetary shadow. In Plato’s Allegory Of The Cave, prisoners mistook shadows for reality until one escaped and saw the true world beyond the cave. Keynes—in a twist of irony—ascended from the cave into the world of economic reality, only to convince his fellow economists that the shadows he had seen on the cave wall were, in fact, the true substance of the economy.

From Substance To Shadows: The Keynesian Sleight Of Hand

Keynesians replaced classical economics with a new worldview that elevated money and credit from shadows to prime movers. The aptly named “Keynesian Revolution” was so profound and far-reaching that the majority of modern economists today would have been classified as crackpots by their pre-1930s counterparts.

For Keynesians, the abstract “symbol economy” of money and credit eclipsed entrepreneurs and tangible goods and services. What is now known as the “macroeconomy”—the lumped, collective whole economy of the nation—became the primary concern, relegating individual economic actors to mere cogs in a vast machine, largely overlooked and deemed powerless against overarching macroeconomic forces.

Demand—not supply—was now seen as the driving economic force; the focus therefore turned toward managing “aggregate demand” and the “animal spirits” that influence it—consumer and business “sentiment”. Monetary factors like government deficits, money supply, credit availability, and taxation—along with the psychology of “animal spirits”—were now viewed as the “real economy” and the primary determinants of economic activity and resource allocation.

By prioritizing symbols over substance, Keynesian thought accelerated our descent into economic hyperreality—a world where “meme magic” shapes economies and markets. Keynes laid the groundwork for our current Financial Matrix, where the manipulation of symbols, shadows, abstract financial constructs, “animal spirits”, and memes takes precedence over the underlying “real” economy.

The Vibes Economy

Keynesian theory has recently been cleverly repackaged for a Gen Z audience in kyla scanlon’s catchy “Vibes Economy” meme, wherein our economic fate is largely determined by the New Age Law Of Attraction. The collective mood of the masses—their “vibes”— dictates the ebb and flow of our economic fortunes; our economic fate is largely self-fulfilling. When the national mood sours into “bad vibes” (😞), we “manifest” a recession or “vibecession”. Conversely, “good vibes” (😊) usher in a booming economy or “vibeboom”—though we must then contend with the specter of inflation.

Taken to its ultimate exaggerated extreme—beyond Keynes’ actual arguments—this implies that the economy is a self-referential hall of mirrors, reflecting back to us our own beliefs and expectations; there is no real, independently existing economic activity to speak of—only a kaleidoscopic landscape of beliefs, emotions, symbols, perceptions, memes, narratives, and “policy responses”. Underlying objective economic reality dissolves, leaving us adrift in a Financial Matrix shaped by little but the prevailing “vibes” and “meme magic”. Economists and policymakers become meme lords and vibe curators, their mission: the manipulation of memes, vibes, statistics, and symbolic equations to steer the collective mood and—by extension—the entire economy.

The Scoreboard Becomes The Game: The Rise Of Macroeconomic Accounting

His education had had the curious effect of making things that he read and wrote more real to him than things he saw. Statistics about agricultural labourers were the substance: any real ditcher, ploughman, or farmer’s boy, was the shadow. Though he had never noticed it himself, he had a great reluctance, in his work, ever to use such words as “man” or “woman.” He preferred to write about “vocational group,” “elements,” “classes,” and “populations”: for, in his own way, he believed as firmly as any mystic in the superior reality of the things that are not seen.

—That Hideous Strength, C.S. Lewis

To operationalize the Keynesian Revolution, a national income accounting system was developed during the Great Depression and World War II. This system—devised with Keynesian theory in mind—grew out of the work of statistically inclined economists such as Colin Clark and Simon Kuznets. The new accounting methodology enabled economists to track economic changes through aggregated statistical measures, leading to the creation of modern metrics like Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and Gross National Income (GNI).

By dealing in these economy-wide totals, our “Economist-Kings” gained the ability to track the flow of money through various sectors of the economy, measuring expenditures by consumers, investors, and government. This approach provided an abstracted macro-level view of economic activity—reinforcing the notion that the economy could be managed and steered like a vehicle—with these aggregate statistics serving as the dashboard indicators.

What Gets Measured Gets Managed: Economic Accounting Enabled Economic Engineering

Economic statistics have been collected and tabulated almost exclusively in the pursuit of seizing the “commanding heights” of the economy and to justify the use of economic engineering to “solve” economic and social “inequality” issues. Just as Mayan or Aztec priests leveraged their exclusive understanding of esoteric celestial phenomena like eclipses to consolidate power and influence, economists have insinuated themselves within the inner circles of government power worldwide through their mastery of arcane economic statistics.

The physical sciences, good and innocent in themselves, had [been] warped, had been subtly manoeuvred in a certain direction. Despair of objective truth had been increasingly insinuated into the scientists; indifference to it, and a concentration upon mere power, had been the result.

—That Hideous Strength, C.S. Lewis

Our modern “priests of economics” collect and interpret statistics ostensibly to address economic challenges and inequality, much like their ancient counterparts observed the heavens to ensure societal well-being. Their Keynesian-inspired prescriptions—based on these arcane figures—provide a scientific veneer to policies politicians intended to pursue anyway.

For example, when measured economic aggregate “output” falls short of its perceived potential, governments and central banks are expected to intervene—akin to how Mesoamerican priests would call for rituals or sacrifices during celestial events. The responses—increasing government spending, expanding the money supply, or borrowing—are the modern equivalent of appeasing the economic gods and “animal spirits” for a bountiful harvest.

The collection and (mis)use of macro statistics have also reinforced and perpetuated a host of pervasive economic fallacies such as the idea that the “consumer is the engine of our economy”—a belief bolstered by the Keynesian focus on “aggregate demand” and the fact that consumption represents two-thirds of GDP. Similarly, it has lent apparent credence to Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz’s erroneous claim that our economy is stuck in “first gear” due to inequality. Stiglitz argues that excessive wealth concentration among too few rich people results in a lower overall “marginal propensity to consume,” thereby supposedly stifling economic dynamism.

Cooking The Books At The Ministry Of Plenty

The use of aggregate economic statistics has not only enabled economic engineering but also opened the door to deliberate manipulation of these figures for political purposes. As these abstract numbers gained primacy in shaping policy and public perception, the temptation to alter them for political gain has proven irresistible. This potential for statistical sleight-of-hand brings to mind a chilling parallel from Orwell’s discussion of the Ministry of Plenty in 1984.

Ostensibly responsible for Oceania’s command economy, MiniPlenty controls the rationing of food, supplies, and goods. However, its true purpose is far more insidious. The Ministry perpetually issues false economic reports, such as claims of increased economic production, even as actual output declines. This deliberate deception maintains the illusion of prosperity and progress, keeping the populace ignorant of their true economic conditions. By manipulating these economic figures, the Party ensures that the citizens remain poor and misinformed, making them easier to control:

But actually, he thought as he re-adjusted the Ministry of Plenty’s figures, it was not even forgery. It was merely the substitution of one piece of nonsense for another. Most of the material that you were dealing with had no connexion with anything in the real world, not even the kind of connexion that is contained in a direct lie. Statistics were just as much a fantasy in their original version as in their rectified version. A great deal of the time you were expected to make them up out of your head. For example, the Ministry of Plenty’s forecast had estimated the output of boots for the quarter at 145 million pairs. The actual output was given as sixty-two millions. Winston, however, in rewriting the forecast, marked the figure down to fifty-seven millions, so as to allow for the usual claim that the quota had been overfulfilled. In any case, sixty-two millions was no nearer the truth than fifty-seven millions, or than 145 millions. Very likely no boots had been produced at all. Likelier still, nobody knew how many had been produced, much less cared. All one knew was that every quarter astronomical numbers of boots were produced on paper, while perhaps half the population of Oceania went barefoot. And so it was with every class of recorded fact, great or small. Everything faded away into a shadow-world in which, finally, even the date of the year had become uncertain.

Echoes of such manipulation resonate in our own world. From creative accounting in GDP calculations to redefining measures of inflation or unemployment, statistical sleight of hand has become a powerful tool for painting a rosier picture of economic performance. These manipulations further divorce our economic discourse from reality, creating a statistical mirage that often bears little resemblance to the economic conditions experienced by ordinary citizens.

Recent events have highlighted the unreliability—if not outright fabrication—of official statistics. As Shrubstack’s Le Shrub wrote this week:

On Wednesday, the Bureau of Labor Statistics released their annual benchmark revision of employment data* (*Every year, the BLS conducts a revision to the data from its monthly survey of businesses’ payrolls, then benchmarks the March employment level to those measured by the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages program).

The revision suggests that there were 818,000 fewer jobs in March 2024 than initially reported.

To put this into context, this is 25% of the annual job formation, and constitutes the largest downward revision since 2009!

Another way of looking at it, when spread through the prior year, the monthly job gain from April 2023 through March 2024 was 173,500 versus 242,000...

Policy makers also came out to to share their “wisdom”:

*BOSTIC: PAYROLL REVISION DIDN’T REALLY CHANGE JOBS VIEW MUCH

Hey Bostic, it didn’t really change our view either….you know why? Because we’ve been highlighting that the data is nonsense for a while now.

Economic statistics have long been wielded as tools for justification rather than elucidation. Historically, policymakers have often cherry-picked or interpreted data to support predetermined stances. Bostic’s statement takes this tendency to a new extreme: the Fed now appears willing to ignore even the government’s own statistics when they contradict the desired policy—inverting Keynes’ own (alleged) principle, and instead adhering to a philosophy of “When the facts change, we maintain our policy. What do you do, sir?”

Hong Kong’s Heretic: Cowperthwaite’s Data-Free Success Story

What gets measured gets managed — even when it’s pointless to measure and manage it, and even if it harms the purpose of the organisation to do so.

Not everyone embraced this new economic orthodoxy. Sir John Cowperthwaite—Hong Kong’s Financial Secretary from 1961-1971, whose policies turned Hong Kong into an economic powerhouse—famously and resolutely refused to compile economic statistics. Cowperthwaite argued that such data was not only unnecessary for managing an economy but would inevitably tempt officials to meddle in the market to address perceived problems, thereby hindering its natural functioning. When asked about the most crucial step poor countries could take to improve their economic growth, Cowperthwaite replied: “They should abolish the office of national statistics.”

The Pseudo-Science Of Economics: When Social Science Plays Dress-Up

While Cowperthwaite’s data-free approach in Hong Kong demonstrated the potential for economic success without extensive statistical analysis, the broader trend in economics moved in the opposite direction. As a result of Keynesianism and the focus on aggregate statistics, economics, finance, and investing have increasingly been shoehorned into—and adopted methods from—the hard sciences.

This “scientistic” approach—applying methods from the hard sciences to social phenomena—has become a foundational building block underpinning our hyperreal Financial Matrix. Complex economic phenomena have been reduced to quantifiable variables and relationships, creating the illusion that they can be modeled and manipulated using applied mathematics or statistics and then “optimized” through “policy responses”.

Hayek’s Warning On Scientism

In his Nobel prize lecture, Friedrich Hayek critiqued not only this flawed scientistic view of economics, but also the problems with the very language that we use to discuss the economy and markets (perhaps exemplified most recently by Ray Dalio’s popular “How The Economic Machine Works”):

… This failure of [economics] is closely connected with [its] propensity to imitate as closely as possible the procedures of the brilliantly successful physical sciences—an attempt which in our field may lead to outright error. It is an approach which has come to be described as the “scientistic” attitude—an attitude which… “is decidedly unscientific in the true sense of the word, since it involves a mechanical and uncritical application of habits of thought to fields different from those in which they have been formed.

The Tyranny of Abstractions: When Economic Symbols Supplant Reality

Over time, our reliance on these Keynesian scientism-inspired economic aggregate statistical “blobs” and oversimplified, abstracted equations—symbolic representations of real-world human actions—has profoundly reshaped not only our economic discourse but our very reality itself. Economic symbols have been reified—transformed from abstract, simplified representations into seemingly objective, real entities that actively shape our world.

Consequently, Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is now “the economy”, the consumer price index (CPI) is “inflation”, US Treasury bonds are the “risk free rate”, volatility is “risk”, the S&P500 is “the market”, and so on.

While we have long since become desensitized to this “new” economics, consider how jaw-droppingly revolutionary this leap truly was. We casually discuss GDP, for instance, as a shorthand for describing an entire economy—and the near-infinite and ever-evolving actions and interactions of the many millions of human beings in it.

But GDP is a single number which fuses data in such a way that it fits one person’s pre-conceived idea of how all of these people in “the economy” are supposed to function! The famous IS-LM model takes this oversimplification even further, attempting to encapsulate the entire macroeconomy with just two intersecting lines on a graph.

The Map Becomes The Territory

After the Keynesian Revolution, economics and finance ceased attempting to analyze the real world and instead began self-referentially analyzing statistical relationships that exist between abstract symbols relative to other abstract symbols that economists themselves had created. In the process, we’ve eliminated from our study and models arguably the most important parts of economics, finance and investing—notably, a focus on individual actions, creative entrepreneurship, and subjective/qualitative information that is impossible to capture quantitatively.

The extreme level of aggregation in scientistic Keynesian economics and national income accounting does more than just conceal the underlying complexity of the economy—it fundamentally distorts our understanding of reality. By condensing the myriad decisions of countless individuals into broad, oversimplified categories, this approach obscures the intricate web of choices and actions made by individual buyers and sellers.

For example, Keynesian economics does not deal with supply and demand in the conventional sense of those terms. Instead, it takes a reductionist view that analyzes the entire private sector in terms of only two categories: consumption goods and investment goods. This extreme aggregation effectively eliminates from consideration the very mechanisms crucial for efficient resource allocation over time—mechanisms that are essential for genuine economic stability and progress.

Living Within Borges’ Hyperreal Map

This reification of economic abstractions has exacerbated our collective hyperreality, wherein symbols and models are mistaken for the underlying reality they were intended to represent—echoing Borges’ fable of an Empire’s map so intricately detailed it was indistinguishable from the territory it represented. Like the citizens in Borges’ tale who continued to inhabit the map long after their Empire collapsed, we ourselves now live within the modeled maps of our economy; we have altogether lost sight of the real-world substance these symbols were supposed to represent.

In our Financial Matrix, abstract economic concepts and symbols have taken on a life of their own—shaping policy decisions and market behaviors in increasingly self-referential ways while blinding us to the actual economic landscape beyond our screens and spreadsheets. This leads to embarrassingly large disconnects between economists and the alleged subjects of their study :

Source: Benjamin Braddock

Source: Unknown

Paul Krugman chimed in to ask with a straight face “Why does the economy look so good to economists but feel so bad to voters?”—and proceed to blame the disconnect on the citizens rather than the economists.

Or, to paraphrase the Simpsons:

Cargo Cult Economics: From Reification To Deification

As we’ve seen, the reification of economic abstractions has led us to mistake our models for reality itself. This confusion between map and territory hasn’t just changed how we view economics—it has fundamentally altered how we practice it. In our reverence for these abstract symbols and equations, economics has undergone a startling transformation: from a tool for understanding human behavior into something resembling a primitive religious cult.

Just as ancient myths provided structuring principles for societies, economic models have been imbued with quasi-religious significance and now serve as the bedrock for our financial and societal worldviews. This transformation has cast economists and “quants” in the role of modern-day priests, interpreting esoteric symbols and equations to divine the mysteries of economies and markets. This deification of quantitative economic expertise further disconnects us from the tangible realities of human action and entrepreneurship, deepening our immersion in the hyperreal Financial Matrix.

As we elevate economic models to the status of sacred texts, we have transformed economics from a tool for understanding human behavior into a primitive religious “cargo cult”:

In the South Seas there is a Cargo Cult of people. During the war they saw airplanes land with lots of good materials, and they want the same thing to happen now. So they’ve arranged to make things like runways, to put fires along the sides of the runways, to make a wooden hut for a man to sit in, with two wooden pieces on his head like headphones and bars of bamboo sticking out like antennas—he’s the controller—and they wait for the airplanes to land. They’re doing everything right. The form is perfect. It looks exactly the way it looked before. But it doesn’t work. No airplanes land. So I call these things Cargo Cult Science, because they follow all the apparent precepts and forms of scientific investigation, but they’re missing something essential, because the planes don’t land.

Like South Seas islanders building grass airports (statistics and mathematical models) and expecting real airplanes (the economy) to land, modern economics comes complete with its own priests, rituals, “spirits”, and unquestionable doctrines. In this economic cargo cult, MiniPlenty economists like Krugman find themselves puzzled by the populace’s dissatisfied “animal spirits”—akin to a cargo cult priest insisting that the plane has indeed landed because all the ritual statistics indicate so—while the islanders frustratingly point out the absence of any actual goods or prosperity in their daily lives. This disconnect exemplifies how deeply entrenched the reification of economic abstractions has become, leading experts to trust their symbolic “landings” over the real world experiences of the people they claim to study.

The Keynesian Architect: Recoding Economic Reality

This cargo cult mentality doesn’t just affect how we understand the economy—it actively shapes it. As we’ve seen, economists often mistake their models for reality. But when these models are used to create policy, they begin to reshape the economic landscape itself. This brings us to an even more profound transformation of our economic reality—one that goes beyond mere misunderstanding to active reconstruction.

In the Matrix, the Architect is an AI program that authored and oversees the simulated reality in which most of humanity unknowingly lives. The Matrix is designed to keep humans docile and controlled while their bodies serve as energy sources for machines.

Keynesian policy now plays a similar role in our Financial Matrix. It doesn’t merely interact with the economy; it fundamentally reshapes it in its own image. While purportedly aiming to stabilize the economy, Keynesian measures actually “Keynesianize” the entire system. Like the Architect programming a controlled environment for humans, Keynesian policies rewrite the rules of our society and ultimately result in our Financial Matrix.

This goes far beyond influencing economic behavior—it alters the very fabric of economic reality. The economy and society start operating on Keynesian principles not because they’re inherently correct, but rather because society has been rewritten with a new Keynesian operating system. Just as humans in the Matrix function within the Architect’s constraints, the entire world now operates within a framework established by Keynesian policies.

This restructuring of economic reality temporarily masks the theory’s fundamental flaws. It becomes nearly impossible to distinguish between “real” economic processes and the artificial constructs created by Keynesian policies. This convoluted interrelationship between theory and policy has long obscured the flaws in Keynesian theory itself.

Coding The Matrix: How Digitization Reshapes Economic Reality

Quantitative methods in economics and finance—enabled by the mechanistic metaphor of the economy and collection of aggregate economic statistics—allowed for the easy digitalization of these abstract symbols. This digitalization—together with our abstract, digitized fiat currency—enabled us to hard code our fallacious beliefs and assumptions about the world directly into the markets themselves and instantaneously reshape the real world in the image of our theoretical models for the first time.

The rise of algorithmic trading and quantitative finance—covered in later installments of this series—has further amplified this abstraction, creating a feedback loop that reinforces our hyperreal Financial Matrix. As economic actors—from central bankers to everyday citizens to automated AI algorithms—internalize “modern” economics concepts and program them into the Financial Matrix, they (temporarily) reshape economic reality to more closely match the model, creating a self-reinforcing cycle of abstraction and financialization; note that this cycle—while temporary in the context of economic history—can persist for decades.

As we continue our exploration of the Financial Matrix, we’ll see how this hyperreal foundation has paved the way for even more profound disconnections from reality.

#multiflation

Great article and thanks for the mention! 🥹🌳🙏

amazing! thanks a lot!