There is a compelling vested interest in euphoria, even, or perhaps especially, when it verges, as in 1929, on insanity. Anyone who speaks or writes on current tendencies in financial markets should feel duly warned. There are, however, some controlling rules in these matters, which are ignored at no slight cost. Among those suffering most will be those who regard all current warnings with the greatest contempt.

—JK Galbraith, The 1929 Parallel, The Atlantic, January 1987 prior to the ‘87 Crash

While Bitcoin treasuries currently represent just one tiny glitch within the sprawling Financial Matrix—and on its face it seems ridiculous to scrutinize them when Fartcoin commands a $1.5 billion market cap—their parallels with the investment trusts of the 1920s nonetheless reveal recurrent speculative pathologies that transcend their current scale. Indeed, they provide a blueprint for reflexive bubbles generally. The shared mechanics between trusts and treasuries therefore offer a perfect lens through which to better understand both financial history and the dynamics currently playing out across the Financial Matrix more broadly.

In Speculative Attack Part I, we explored how Michael Saylor’s MicroStrategy is weaponizing Wall Street's own financial engineering against the TradFi system by inverting the Alchemy Of Risk; hundreds of companies now race to copy his blueprint.

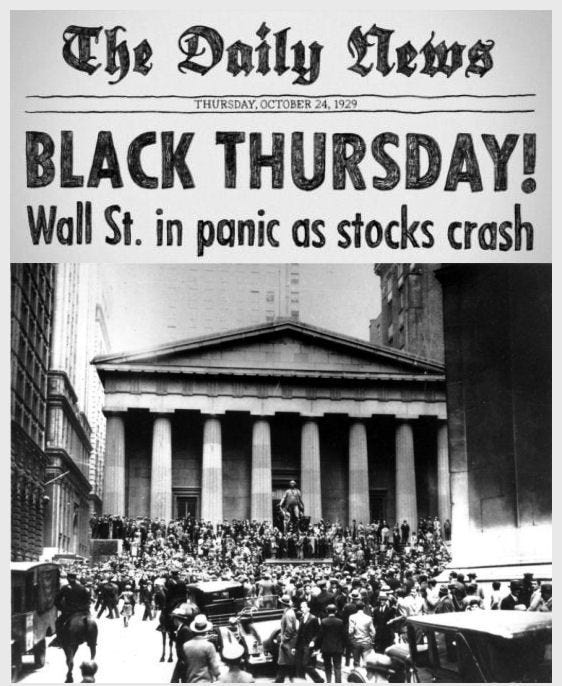

Speculative Attack Part II examined similarities between today’s Bitcoin treasuries and the “investment trusts” of the 1920s. These trusts emerged as corrupted versions of established, well-respected British investment vehicles that American financiers amplified with leverage. By mid-1929, the trust mania had reached its crescendo. Goldman Sachs Trading Corporation had become the MicroStrategy of its day, and new trusts launched at a rate of one per day as investors eagerly paid double or triple the value of their underlying “scarce” assets.

Yet how could something as futuristic as Bitcoin treasuries share any lineage with the financial trusts of the 1920s—an era untouched by computers, let alone the blockchain, in the years before the SEC had even been formed, much less begun to rein in Wall Street's more colorful abuses? At first glance, the structural differences between 1929’s trusts and today’s treasuries seem both obvious and inevitable.

They are—we argue—largely beside the point. Every era in financial history unfolds with its own distinctive features within its own unique context. The obsessive focus on surface-level distinctions is a perennial human rationalization for dismissing legitimate warnings about emerging financial risks and excesses based on historical lessons. Market participants approach each episode as if it were humanity's first encounter with Financial Alchemy, ignoring the “warning for posterity” chronicled in Great Mirror Of Folly (1720). This approach is not unlike preparing to fight the last war, however, rather than grappling with the enduring principles of warfare and applying them to the battles at hand.

Recent decades have seen this pattern manifest clearly in everything from ‘private credit’ to trillions in negatively yielding bonds to the historic housing bubbles that infected—and are now seemingly being purged—in Australia, Canada, Sweden, and the UK. In the case of those housing bubbles, for example, market participants dismissed concerns by pointing to the absence of complex American-style derivatives like CDOs, NINJA loans, rampant fraud, non-recourse lending, and bank failures during the 2008 Crisis. Like champagne purists who demand provenance from the correct French hillside, many now believe a housing bubble can only exist if it features the exact trappings of the subprime crisis as popularized by The Big Short—complete with CDO-cubed managers eating sushi in Vegas:

The result is a kind of historical literalism: structural differences are taken as proof of safety, when in fact they are often overstated, misleading, or fundamentally irrelevant. In practice, for example, each of the aforementioned countries simply developed its own distinctive mechanisms that serve analogous alchemical functions.

Bitcoin treasury proponents make a parallel argument when they contend that comparisons to 1920s investment trusts are fundamentally flawed: whereas the trusts were built atop opaque pyramids, hidden leverage, and fee extraction in an unregulated market, Bitcoin treasuries are transparent single-entity corporations without a management fee layer, subject to modern SEC disclosure rules and holding the most desirable mark-to-market asset in existence. In short, they argue that any superficial similarities mask profound differences in structure, agency, and information flow.

While we agree with some—if not many—of these points, we nonetheless arrive at a different conclusion. The remarkable fact is not that such differences exist between Bitcoin treasuries and 1920s trusts, but that the same fundamental dynamics repeatedly emerge regardless—making the deeper parallels between them impossible to ignore. Both feature massive mNAV premiums, “accretion magic”, and reflexive feedback loops where purchases drive up the underlying asset prices, increasing their own value and borrowing power. Investors in both eras embraced “intelligent” long-term leverage and the seductive promise of easy money through financial alchemy to capitalize on a “sure thing” bet.

These patterns represent more than mere historical parallels—they expose the immutable aspects of human nature and financial reflexivity that underpin credit bubbles generally, transcending both era and asset. The fate of those earlier trusts therefore provides a dispassionate lens through which to view not only the emerging Bitcoin treasury phenomenon, but the recurring dynamics of financial alchemy that define bubble formation across centuries of market history.

Twitter/X: @bewaterltd. Suggestions? Feedback.

Not investment advice. For educational/informational purposes only. See Disclaimer.

“Investment Trusts Multiplied Like Locusts”

The explosive proliferation of Bitcoin treasury companies mirrors that of the 1920s investment trusts, and both gold rushes stem from a perfect storm of greed: intense investor demand for exposure to a scarce asset creates mNAV premiums that promoters rush to monetize. If Goldman Sachs could extract enormous profits from its trust in the 1920s, why couldn’t everyone else? If MicroStrategy can monetize its mNAV premium, why shouldn’t every other company follow suit?

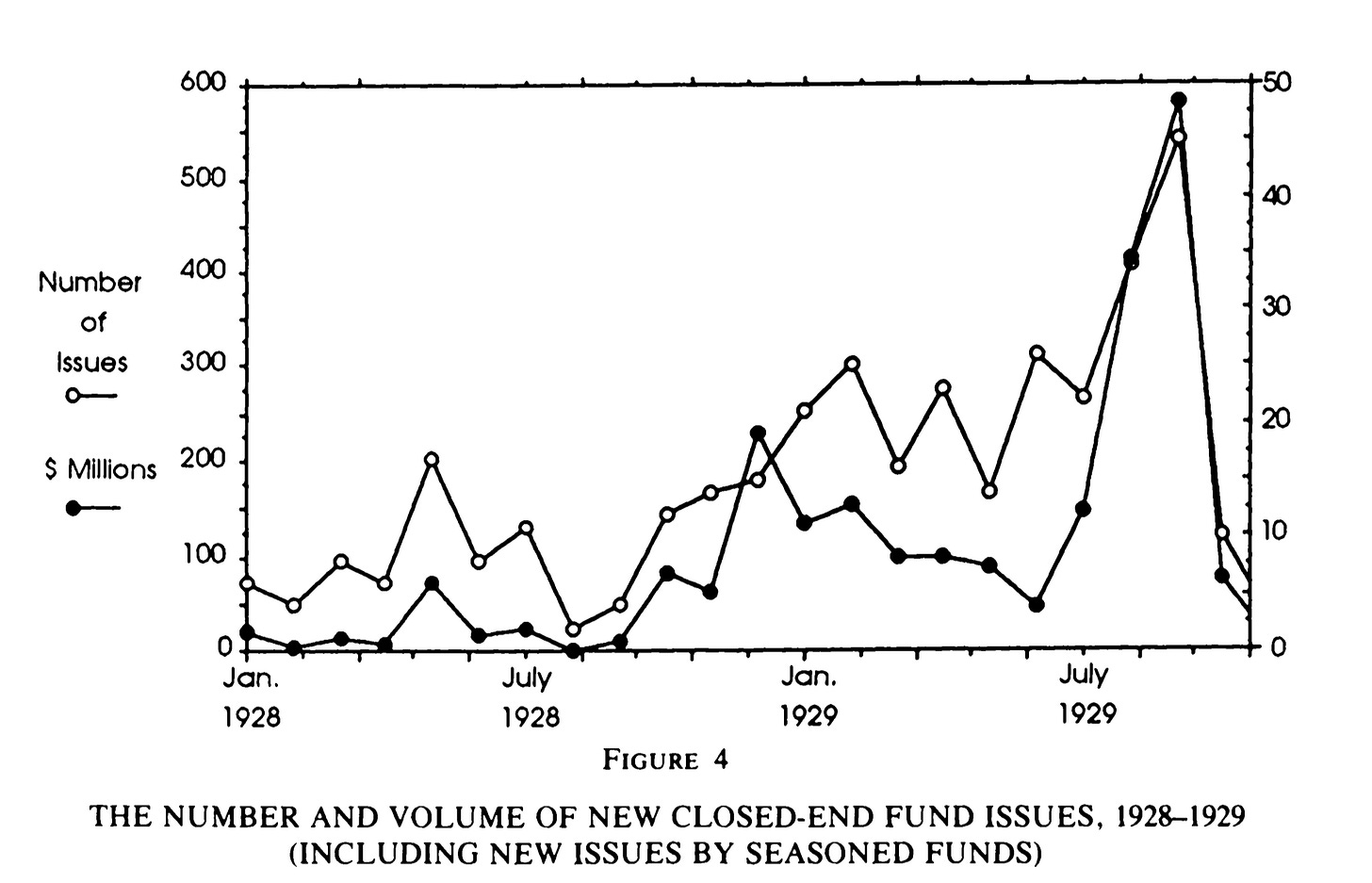

Galbraith documented the explosive growth of trusts in the 1920s:

During 1928, an estimated 186 investment trusts were organized. By the early months of 1929, they were being promoted at the rate of approximately one each business day, and a total of 265 made their appearance during the course of the year.

The dollar volumes of capital raised tell an equally dramatic story, accounting for 70% of all funds issued in the 1920s. New trust issuance during August and September 1929 alone amounted to $1bil—equivalent in today’s purchasing power to perhaps $20bil, or $130 billion as a proportion of today’s economy:

In 1927, the trusts sold to the public about $400,000,000 worth of securities. In 1929, they marketed an estimated three billion dollars' worth. This represented at least a third of all new capital issues in that year.

By the autumn of 1929, the total assets of the investment trusts were estimated to exceed eight billion dollars. They had increased approximately elevenfold since the beginning of 1927.

Frederick Lewis Allen’s account corroborates Galbraith’s; in Only Yesterday: An Informal History of the Nineteen Twenties, Allen vividly described how “investment trusts multiplied like locusts”:

There were now said to be nearly five hundred of them, with a total paid-in capital of some three billions and with holdings of stocks—many of them purchased at the current high prices—amounting to something like two billions. These trusts ranged all the way from honestly and intelligently managed companies to wildly speculative concerns launched by ignorant or venal promoters.

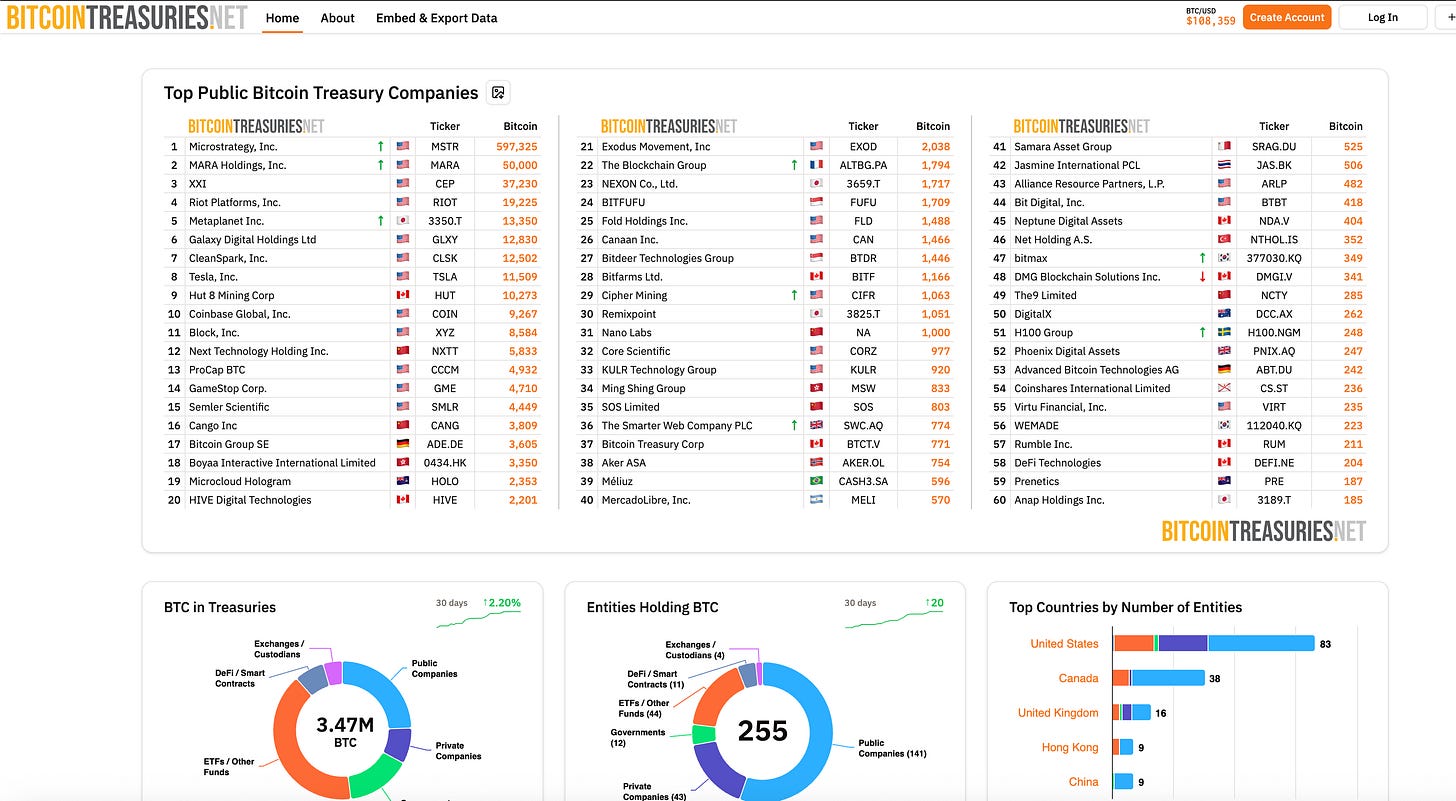

Bitcoin Treasuries’ Cambrian Explosion

Today's Bitcoin treasuries show a remarkably similar pattern; new entities launch weekly as companies around the world race to replicate MicroStrategy's success. The Bitcoin treasury Cambrian explosion is trackable in real-time via a web dashboard:

Golden Age Of Grift

What began as innovation quickly became exploitation. Galbraith and Allen emphasize that this was not an era of isolated bad actors, but a systemic opening for opportunism fueled by rising prices and vanishing ethics.

The most lucrative role in the trust boom wasn’t investor—it was promoter. Galbraith makes clear that insiders extracted value both upfront and continuously through fees, while public buyers bore the ultimate risk:

The enthusiasm with which the public sought to buy investment trust securities brought the greatest rewards of all. Almost invariably people were willing to pay a sizable premium over the offering price. The sponsoring firm (or its promoters) received allotments of stock or warrants which entitled them to stock at the offering price. These they were then able to sell at once at a profit.

New issues were typically issued to insiders or to favored customers at prices slightly above the net asset value, but many of them quickly rose to a large premium. For example, Lehman Brothers Corporation was significantly oversubscribed at $104 per share that bought $100 in assets (but note that its management contract gave 12.5 percent of profits to Lehman Brothers as a management fee; its true net asset value was perhaps $88). It immediately rose to $126 per share in open trading. The organizers collected not only $4 per share and large future management fees, but they were also significant initial investors at more favorable terms than those available to the public, and they reserved the right—not valuable if the fund is selling at a discount, but valuable if it is selling at a premium—to take their fee in the form of new shares purchased at current net asset value.

Like the 1920s trusts, today’s Bitcoin treasury companies often feature similar arrangements—founder allocations, insider stock options, and incentive packages for promoters and podcasters. This time, however, such mechanics are disclosed under SEC rules designed in response to the very abuses of the 1920s. But transparency neutralizes neither risk nor incentive distortions:

The speculative fervor and sheer velocity of trust formation in the 1920s provided perfect cover for abuse by promoters with less than honorable intentions. The proliferation of dodgy investment trust and holding company structures exemplified what Galbraith saw as a broader pattern of financial excess during the 1920s. American enterprise “had welcomed an exceptional number of promoters, grafters, swindlers, impostors, and frauds," creating what Galbraith described as "a kind of flood tide of corporate larceny." Allen concurred:

One could indulge in all manner of dubious financial practices with an unruffled conscience so long as prices rose. The Big Bull Market covered a multitude of sins. It was a golden day for the promoter, and his name was legion.

These observations resonate with other manic periods of financial speculation and fraud, including today's Golden Age of Grift, and historical episodes such as John Law’s Mississippi Bubble—discussed in our Alchemy of Risk series and satirically chronicled in The Great Mirror Of Folly (1720). But beneath the outright frauds was another kind of risk—less visible, perhaps, but no less dangerous: the structural Alchemy of Risk inherent to the trusts’ capital structure design.

Financial Alchemy

Some call it alchemy. I call it valuation.

—Phong Le, CEO MicroStrategy

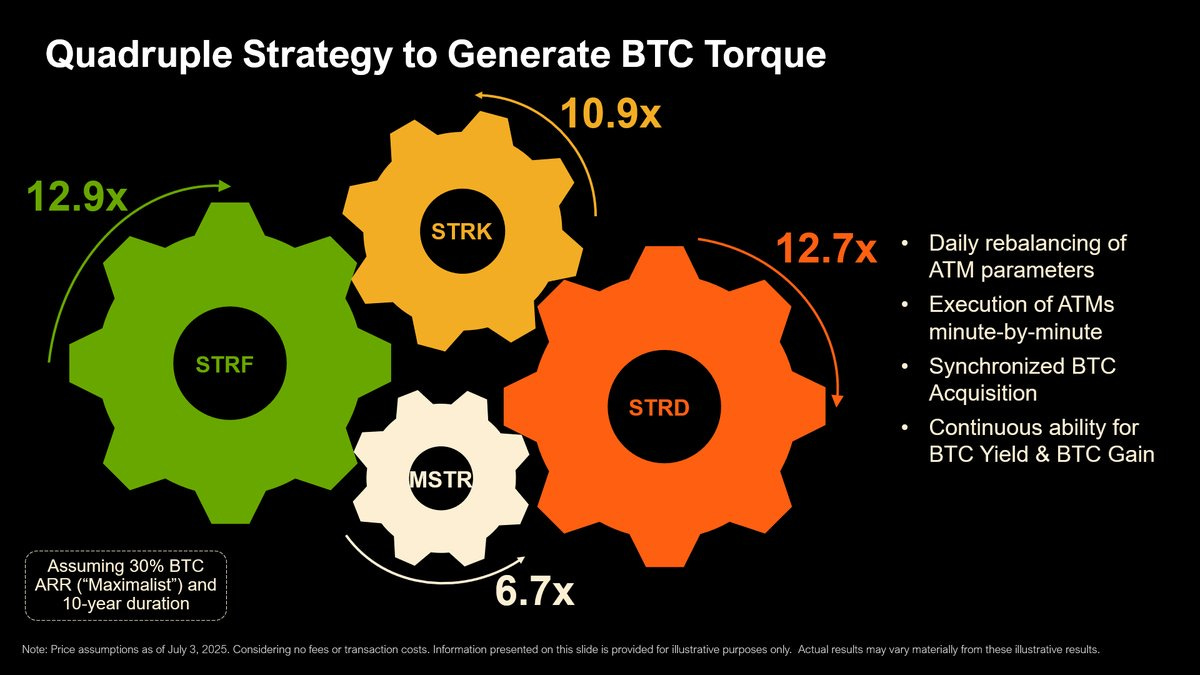

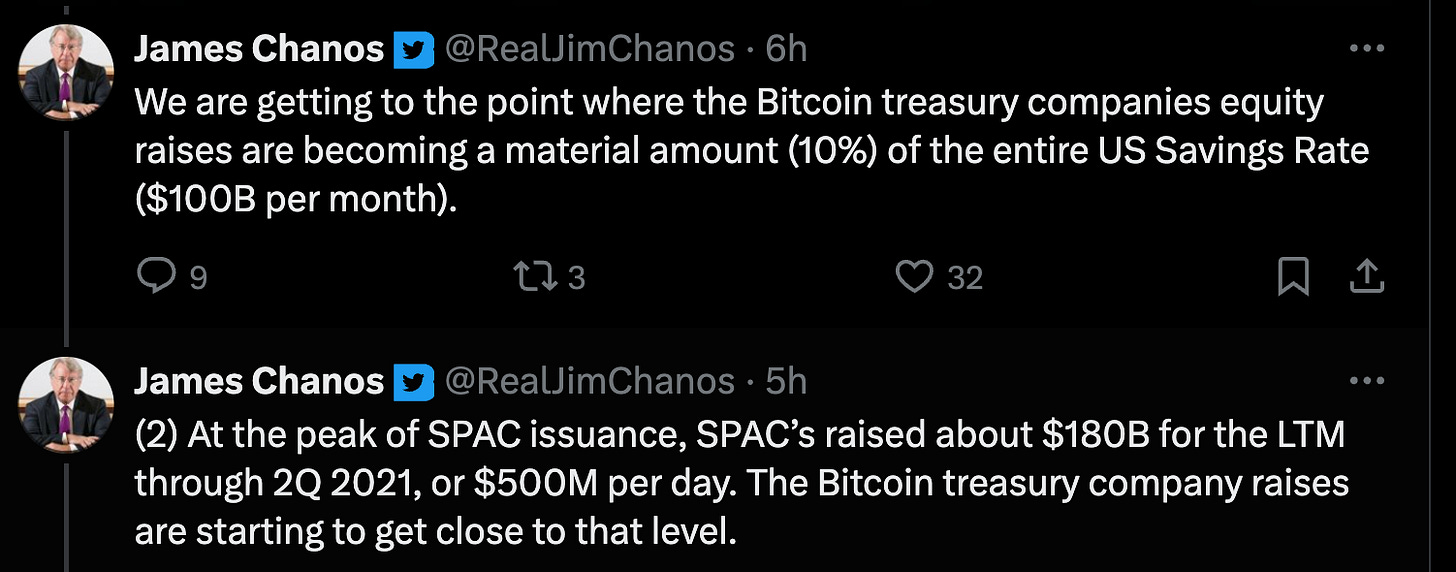

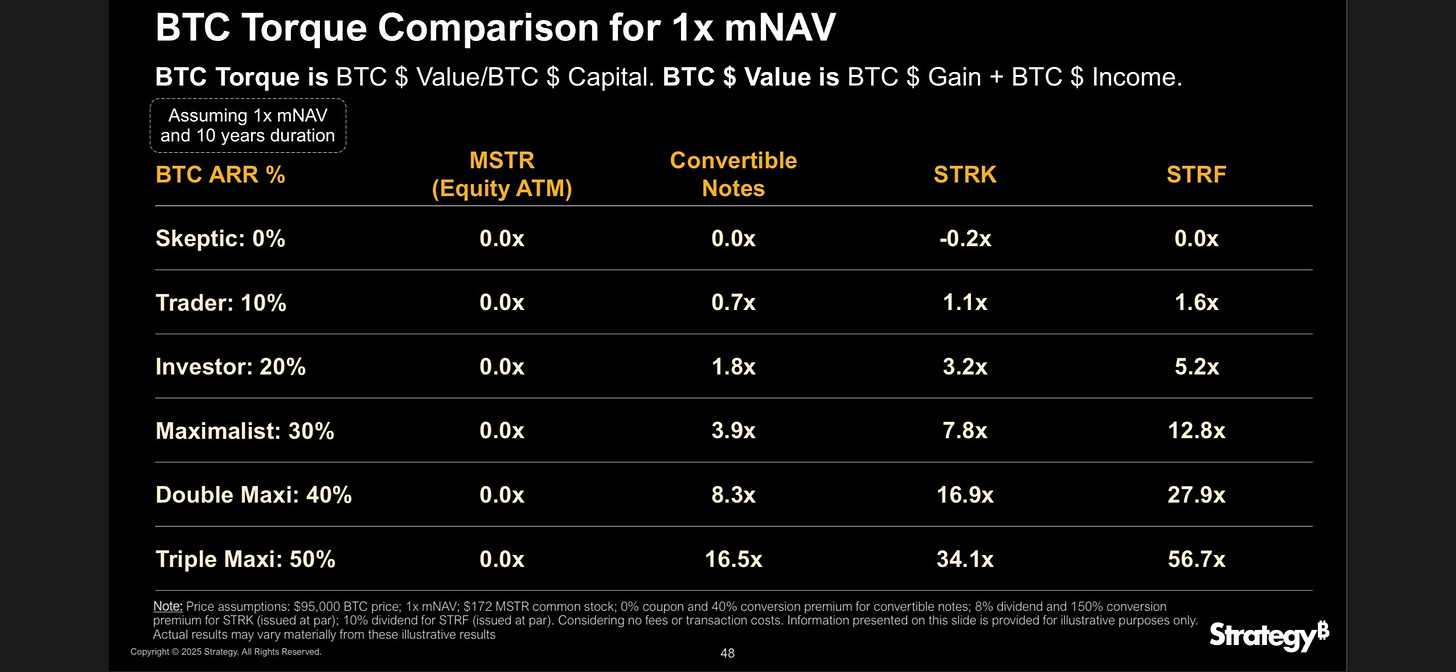

MicroStrategy helpfully provides a video and table showing the “torque”—essentially the amplified exposure to Bitcoin price movements—for different layers of its capital stack (equity, convertible notes, preferred shares, etc.):

Michael Saylor rebuts comparisons to closed-end funds such as GBTC (see Part II, here) by pointing to MicroStrategy’s significantly greater flexibility as an operating company:

Sometimes I see..a Twitter analyst saying, oh, this is just like when GBTC and Grayscale went below one times mNAV before. And what they miss is that Grayscale [GBTC] was a closed-end [fund]. And we're an operating company.

A [fund like GBTC]…has no operational flexibility to manage its capital structure…it doesn't have the option to refinance or take on leverage or to sell securities, buy securities, recapitalize, or buy their own stock back.

Operating companies [like MicroStrategy] have much more flexibility. We can buy stock, sell stock, recapitalize. We can take on debt to fix or to close a gap.

This distinction, however, overlooks a certain historical irony: the investment trusts of the 1920s pioneered the very capital structure innovations that make today's Bitcoin treasury companies so compelling to investors—and created the same reflexive dynamics in the 1920s that we observe today.

As Galbraith documented, the investment trust had evolved into something far more sophisticated than a simple pooled investment vehicle such as GBTC—it had become a flexible corporate structure of exactly the type about which Saylor boasts today:

The investment trust became, in fact, an investment corporation. It sold its securities to the public—sometimes just common stock, more often common and preferred stock, debenture and…bonds—and the proceeds were then invested as the management saw fit. Any possible tendency of the common stockholder to interfere with the management was prevented by selling him non-voting stock or having him assign his voting rights to a management-controlled voting trust.

The Investment Company Act of 1940 specifically curtailed these practices precisely because they had proven so effective—and so dangerous—during the market speculation that preceded the 1929 Crash. When Greyscale and their attorneys structured GBTC, they likely chose its format—at least in part—to avoid registering under the “40 Act.” The inability for funds like GBTC to deploy MicroStrategy’s full suite of tools is not an inherent limitation, but rather the result of deliberate SEC policies intended to prevent a repeat of the 1920s investment trust excesses and their aftermath.

The capital structure of 1920s trusts is virtually indistinguishable from MicroStrategy today: both issue securities—equity at an mNAV premium, bonds, convertible bonds, and preferred stock—to attract investors with varying risk (“torque”) appetites and need for income. The convertible bonds that were central to MicroStrategy’s funding strategy, for instance, were also a hallmark of the 1920s trusts that Allen documented in his research:

It became fashionable to give [new bonds issued by the trusts] a palatably speculative flavor by making them convertible into stock or by attaching to them warrants for the purchase of stock at some time in the rosy future.

The business model of many investment trusts during the 1929 boom was rooted less in asset management than in financial alchemy. Complex capital structures and layers of leverage were not merely passive funding tools to enhance returns—they were the core of the enterprise. The objective was to conjure an endless supply of speculative securities to satisfy insatiable public demand. That demand was fueled by the belief—captured by Galbraith—that the underlying stocks purchased by the trusts had acquired a kind of “scarcity value,” and that the most desirable stock issues were on the verge of disappearing from the market entirely.

What the public was buying wasn’t simply access to a diversified portfolio of scarce stocks, however, but rather a wager on the performance of the trust’s own financial alchemy: the real "product" was the trust's own securities and mNAV. They were the alchemical laboratories that transmuted the public's desire for speculative gains into new securities conjured out of thin air.

Intelligent, Long-Term Debt

This proto-MicroStrategy approach gave 1920s trust managers access to premium forms of leverage: corporate bonds with long durations—sometimes up to 30 years—rather than margin or “call” loans subject to immediate liquidation. These extended maturities theoretically allowed the trusts to maintain leverage across business cycles without facing immediate refinancing pressure, while their relatively low yields reflected widespread investor complacency and a systematic mispricing of risk.

Lyn Alden makes similar observations about contemporary Bitcoin treasury companies:

Publicly-traded operating corporations have access to better types of leverage than hedge funds and most other types of capital. Specifically, they have the ability to issue corporate bonds…often with multi-year durations. If they hold bitcoin and the price dips, they don’t have to sell prematurely. This gives them a better ability to weather periods of volatility than entities that rely on margin loans. There are still bearish scenarios that could force corporations to liquidate, but those scenarios would involve a much longer bear market occurring, thus making them less likely.

Long-Term Debt And Reflexivity

Lyn's analysis above—while accurate for any individual company in isolation—overlooks the systemic risk that emerges when these "safer" leverage structures proliferate. Just as long-term 30 year mortgages didn’t prevent the 2008 crisis, any long-duration debt doesn't inherently eliminate systemic risk; it may even amplify it.

During the boom years of the late 1920s, financial alchemy magnified returns through the same self-fulfilling prophecy that benefits Bitcoin treasuries today: rising asset prices and mNAV premiums enabled more leverage and “torque”, which in turn pushed asset prices higher still. But this reflexive loop made the system inherently unstable. As we saw, these complicated capital structures were far more than passive funding instruments—they played an integral role in fueling both the bubble's spectacular inflation and its subsequent collapse.

Like cheap hurricane insurance after a series of quiet storm seasons that spurs a building boom, the apparent safety of termed-out debt in a bull market may encourage more leverage, creating larger positions and asset inflation that ultimately amplify downside volatility rather than dampen it. The newfound availability of "affordable" protection against forced liquidation triggers a spectacular expansion of risk-taking along the waterfront—until the inevitable hurricane arrives and the insurance marketplace itself collapses. When hundreds or thousands of companies adopt the same capital structure and business model of speculating on a “one way bet”, what appears individually prudent can easily become collectively destabilizing. In financial “progress”, the dose makes the poison.

Path Dependency & Pyramid Schemes

Like some of the more egregious mortgages of 2005-2006 vintage that were practically designed to default on the first payment, towards the end of the 1920s bubble many investment trusts effectively launched from inception as de facto pyramid schemes—dependent on new inflows or price appreciation to meet obligations—despite holding diversified portfolios of dividend-paying stocks and interest-bearing bonds:

Some of them…were so capitalized that they could not even pay their preferred dividends out of the income from the securities which they held, but must rely almost completely upon the hope of profits.

This created a precarious dependency: to pay their bondholders and preferred shareholders, the trusts had to either issue new shares—relying on their mNAV premiums—or count on future portfolio appreciation. These two mechanisms were reflexively intertwined: portfolio gains drove higher mNAV premiums, which in turn enabled more share issuance that funded further portfolio expansion.

In essence, they were using new investor money or future price appreciation to pay existing obligations—the classic structure of a pyramid scheme—making them vulnerable to market downturns when new capital dried up and portfolio gains evaporated, causing their mNAV premiums to collapse in a self-reinforcing spiral.

Because Bitcoin treasury companies (currently) have no cash flow, they tend to follow a similar playbook in that they raise money from investors to pay their obligations:

Like the 1920s trusts, this pyramid-like strategy functions effectively while Bitcoin appreciates, the companies maintain their mNAVs, and the capital markets remain open to them. However, if all of these conditions deteriorate simultaneously for an extended period—possibly as the result of an over-proliferation of leveraged Bitcoin treasuries themselves—these companies would face the same structural vulnerabilities that devastated the 1920s trusts.

Indeed, one major difference between 1920s investment trusts and today's Bitcoin treasury companies lies in what they actually own. The trusts held (seemingly) diversified portfolios of dividend-paying stocks and interest-bearing bonds that generated cash flows to service their preferred shares and bonds—at least until the Great Depression revealed that they were all correlated due to the nature of the pervasive credit bubble.

While "hyperbitcoinization" and "Bitcoin banks" may offer future opportunities to change this dynamic, Bitcoin currently generates no cash flows, pays no dividends, and yields no interest. This creates a structural vulnerability that the 1920s trusts, for all their flaws, did not face. Bitcoin treasuries, lacking even the income streams of 1920s trusts, tend to be more vulnerable to these pyramid dynamics—not less. Their viability—even within the context of a long term bull market during which Bitcoin appreciates tenfold—is entirely path-dependent, hinging on continued appreciation, access to credit, and investor enthusiasm. Break the chain—possibly by oversaturation of leveraged bitcoin treasuries themselves—and the structure unravels, as we will discuss in the forthcoming Part IV of the series.

The Collapse Of The Trusts And The 1929 Crash

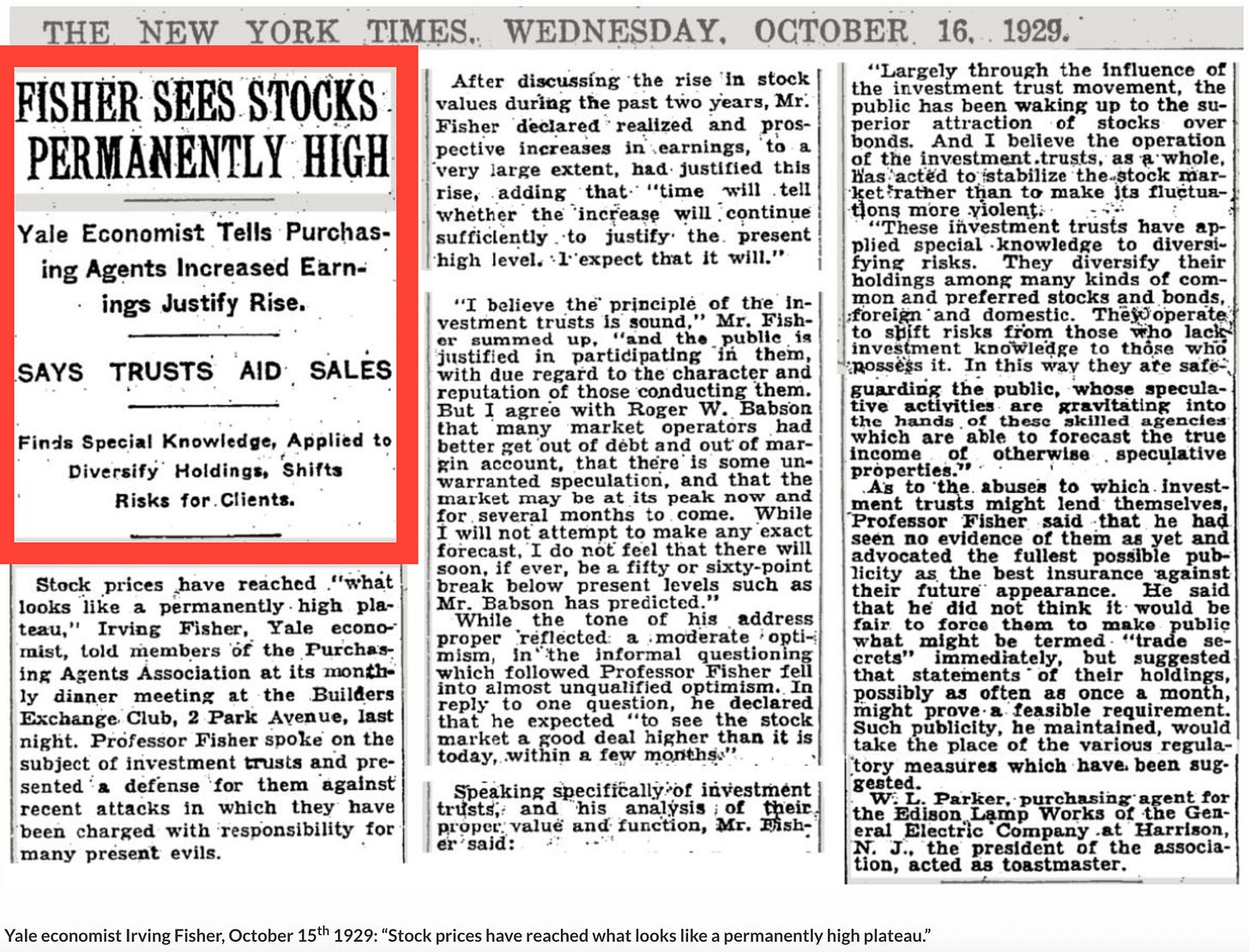

The renowned Yale economist Irving Fisher famously declared that stock prices had reached a "permanently high plateau" just prior the 1929 Crash. Fisher's declaration exemplified the kind of euphoric confidence that typically marks a market top. Even the most ardent Bitcoin bulls should—in the short-term, anyway—beware similarly sweeping proclamations:

Fisher's plateau quote is now infamous, but the lesser-known context that gave rise to it tells a more revealing story. He was actually defending investment trusts as a key support for stock valuations, much as Bitcoiners cite built-in demand from Bitcoin treasuries today. The New York Times reported at the time:

Professor Fisher spoke on the subject of investment trusts and presented a defense for them against recent attacks in which they have been charged with responsibility for many present evils.

Fisher defended trusts on the grounds that these vehicles were awakening people to the superiority of stocks over bonds and providing investors with a superior structure for gaining equity exposure—much as Bitcoin treasury advocates today claim MicroStrategy offers turbocharged “torque” over direct Bitcoin ownership, and Bitcoin itself offers superiority over TradFi assets like fiat currency, stocks, bonds, and real estate:

I believe the principle of the investment trusts is sound, and the public is justified in participating in them, with due regard to the character and reputation of those conducting them. Largely through the influence of the investment trust movement, the public has been waking up to the superior attraction of stocks over bonds. And I believe the operation of the investment trusts, as a whole, has acted to stabilize the stock market rather than to make its fluctuations more violent.

Reflexivity Is A Two-Way Street!

The Crash wasn't merely a price event—as the reflexive loop reversed, the same dynamics that drove the boom amplified the bust both in the asset markets and the real economy. The investment trusts, which Irving Fisher had only a week before championed as guaranteeing a "permanently high plateau" of stock values, became primary agents of this destruction:

By now it was also evident that the investment trusts, once considered a buttress of the high plateau and a built-in defense against collapse, were really a profound source of weakness. The leverage, of which people only a fortnight before had spoken so knowledgeably and even affectionately, was now fully in reverse.

With remarkable celerity it removed all of the value from the common stock of a trust. As before, the case of a typical trust, a small one, is worth contemplating. Let it be supposed that it had securities in the hands of the public which had a market value of $10,000,000 in early October. Of this, half was in common stock, half in bonds and preferred stock. These securities were fully covered by the current market value of the securities owned. In other words, the trust's portfolio contained securities with a market value also of $10,000,000.

A representative portfolio of securities owned by such a trust would, in the early days of November, have declined in value by perhaps half. (Values of many of these securities by later standards would still be handsome; on November 4, the low for Tel and Tel was still 233, for General Electric it was 234, and for Steel 183.) The new portfolio value, $5,000,000, would be only enough to cover the prior claim on assets of the bonds and preferred stock. The common stock would have nothing behind it. Apart from expectations, which were by no means bright, it was now worthless. This geometrical ruthlessness was not exceptional. On the contrary, it was everywhere at work on the stock of the leverage trusts. By early November, the stock of most of them had become virtually unsalable. To make matters worse, many of them were traded on the Curb or the out-of-town exchanges where buyers were few and the markets thin.

Frederick Lewis Allen's account again corroborates Galbraith's account:

Fear, however, did not long delay its coming. As the price structure crumbled there was a sudden stampede to get out from under. By eleven o’clock traders on the floor of the Stock Exchange were in a wild scramble to “sell at the market.” Long before the lagging ticker could tell what was happening, word had gone out by telephone and telegraph that the bottom was dropping out of things, and the selling orders redoubled in volume. The leading stocks were going down two, three, and even five points between sales. Down, down, down. . . . Where were the bargain-hunters who were supposed to come to the rescue at times like this? Where were the investment trusts, which were expected to provide a cushion for the market by making new purchases at low prices? Where were the big operators who had declared that they were still bullish? Where were the powerful bankers who were supposed to be able at any moment to support prices? There seemed to be no support whatever. Down, down, down. The roar of voices which rose from the floor of the Exchange had become a roar of panic.

It should therefore never be forgotten that reflexivity cuts both ways, and can impact the fundamentals of the underlying assets—not just their market prices:

The most important corporate weakness was inherent in the vast new structure of holding companies and investment trusts. The holding companies controlled large segments of the utility, railroad, and entertainment business. Here, as with the investment trusts, was the constant danger of devastation by reverse leverage. In particular, dividends from the operating companies paid the interest on the bonds of upstream holding companies. The interruption of the dividends meant default on the bonds, bankruptcy, and the collapse of the structure. Under these circumstances, the temptation to curtail investment in operating plant in order to continue dividends was obviously strong. This added to deflationary pressures. The latter, in turn, curtailed earnings and helped bring down the corporate pyramids. When this happened, even more retrenchment was inevitable. Income was earmarked for debt repayment. Borrowing for new investment became impossible. It would be hard to imagine a corporate system better designed to continue and accentuate a deflationary spiral…

The stock market crash was also an exceptionally effective way of exploiting the weaknesses of the corporate structure. Operating companies at the end of the holding-company chain were forced by the crash to retrench. The subsequent collapse of these systems and also of the investment trusts effectively destroyed both the ability to borrow and the willingness to lend for investment. What have long looked like purely fiduciary effects were, in fact, quickly translated into declining orders and increasing unemployment.

The crash didn't merely destroy paper wealth—it revealed the bad investments in the real economy that had been masked by debt-driven asset price inflation and forced a painful liquidation of unsustainable business models and debt structures.

Bitcoin treasuries face the same risk, even within the context of a structural, long-term bull market. If Bitcoin falls substantially—possibly as a result of excess leverage and speculation emanating from the treasury companies themselves—and the treasuries trade at discounts to NAV for a prolonged period of time, the common equity could be wiped out just as it was for the trust shares of 1929 despite their “safe” termed out leverage. Further, as we will discuss in Part IV, a proliferation and then implosion of Bitcoin treasuries could even negatively impact Bitcoin adoption itself for a period of time.

Live By The mNAV, Die By The mNAV

If [we’re] an operating company and we trade below NAV, we just get to monetize that—that's good for me.

Saylor’s confidence in monetizing NAV discounts—which is perhaps reasonable for MicroStrategy in isolation—mirrors the same logic 1920s trust managers used to justify buybacks—only to find that such support strategies are ineffective when liquidity across the ecosystem vanishes and selling pressure dominates.

The trusts discovered that buying back shares when investors are selling and credit is tightening is vastly different from issuing shares when investors are buying. Desperate to prop up their stock prices, the trusts began buying back shares at a discount to NAV—a strategy Bitcoin treasury companies will likely adopt with equally disappointing results for most:

The stabilizing effects of the huge cash resources of the investment trusts had also proved a mirage. In the early autumn the cash and liquid resources of the investment trusts were large...But now, as reverse leverage did its work, investment trust managements were much more concerned over the collapse in the value of their own stock than in the adverse movements in the stock list as a whole…

Under these circumstances, many of the trusts used their available cash in a desperate effort to support their own stock. However, there was a vast difference between buying one's stock now when the public wanted to sell and buying during the previous spring—as Goldman Sachs Trading Corporation had done—when the public wanted to buy and the resulting competition had sent prices higher and higher. Now the cash went out and the stock came in, and prices were either not perceptibly affected or not for long. What six months before had been a brilliant financial maneuver was now a form of fiscal self-immolation. In the last analysis, the purchase by a firm of its own stock is the exact opposite of the sale of stocks. It is by the sale of stock that firms ordinarily grow.

As the crisis deepened and the mNAV continued to trade at a discount, trusts depleted their remaining cash reserves in a desperate—and ultimately self-defeating—effort to support collapsing share prices:

However, none of this was immediately apparent. If one has been a financial genius, faith in one's genius does not dissolve at once. To the battered but unbowed genius, support of the stock of one's own company still seemed a bold, imaginative, and effective course. Indeed, it seemed the only alternative to slow but certain death. So to the extent that their cash resources allowed, the managements of the trusts chose faster, though equally certain death. They bought their own worthless stock. Men have been swindled by other men on many occasions. The autumn of 1929 was, perhaps, the first occasion when men succeeded on a large scale in swindling themselves.

Conclusion

The 1920s investment trust mania offers a generalized blueprint for understanding financial bubbles built on leverage, reflexivity, and the allure of premium-to-NAV accretion magic. What began as financial innovation soon metastasized into speculative instruments that promised effortless wealth through financial alchemy. When the music stopped, the reflexive mechanisms that had driven prices to euphoric heights accelerated their catastrophic descent.

The parallels with today's Bitcoin treasury companies are striking—from the proliferation of new entities to the reliance on mNAV premium to the use of long-term debt to amplify returns. Just as the 2008 Crisis was not primarily the result of subprime, CDOs, and mortgage fraud—as we explored in the Tower Of Babel—the investment trusts of the 1920s didn’t primarily collapse because of fraud, bad bets, lack of transparency and regulatory oversight, or their sometimes interlocking or pyramided holdings. They collapsed because their very success—built upon the Alchemy Of Risk—reflexively contained within it the seed conditions for their future failure; Bitcoin treasuries may be walking the same path toward the same precipice.

More concerning, however, is that just as the 1920s trusts signaled the speculative excesses of their era, Bitcoin treasuries are symptomatic of today’s Multiflation—a far deeper disease distorting today’s economic order. The emergence of a recently filed gold-backed treasury company suggests that Saylor and Bitcoin treasury companies' speculative attack on fiat currency is expanding beyond Bitcoin:

This broader assault on monetary orthodoxy may signal an incipient "flight into real values" (Flucht in die Sachwerte)—one that threatens to escalate into a full-fledged war against the financial establishment. Indeed, the gold treasury company's actual business model—tokenizing commodities markets—could accelerate this trend by channeling additional money and credit into the real economy. Rather than containing inflationary pressures safely within the virtual casino of the Financial Matrix, this risks adding further fuel to an inflation super-cycle.

Up Next: Can Bitcoin Break The Curse Of Reflexivity?

In Part IV, we offer a customizable ChatGPT Prompt for experimenting with your own Bitcoin Treasury and Digital Asset Treasury assumptions:

In Part V, we'll examine whether Bitcoin’s unique monetary properties—colliding with central bank money printing on an unprecedented scale—might enable levered treasury companies to reverse the historical pattern entirely through financial jiu jitsu: triggering a reflexive speculative attack against fiat, and creating a self-fulfilling prophecy that resembles a “run on the bank”. Or whether, like the investment trusts of the 1920s, they carry within their structure the same seeds of systemic fragility for the Bitcoin ecosystem.

Great article bruv! I wonder how this will end 🤭

Truly an excellent read, and a wonderful analogy.

The treasury strategy still feels in its 3rd innings here though. If so, then this has legs.

Perhaps the burst comes when the Michael Howell liquidity drops off into 2026. In the meantime, this thing has the potential to be much much bigger.

So the question is, knowing this, do you want to dance, and if you do dance do you know when to stop?