By midnight the conference room had transformed into something resembling a detective's command center. Documents were organized in piles with color-coded sticky notes. Every inch of the whiteboard was plastered with merger agreement clauses, board member connections, and detailed analyses. Nigel stood before this maze of information, marker in hand, eyes gleaming as he glimpsed the solution to the puzzle.

"So," he asked, turning to face us. "How do they get out of this deal without actually walking away from it?"

Within months of that evening’s masterclass, the process and philosophy Nigel taught us would become essential to our survival as credit markets seized and merger after merger collapsed during the Financial Crisis.

Today, as we navigate Multiflation’s disorder, Nigel’s lessons remain equally valuable. Merger arbitrage serves three purposes within our Multiflation Method: merger spreads function as a barometer of liquidity and the ways in which Multiflationary forces are reshaping the economy; where we previously identified Archetypes that thrive under multiflation, announced deals provide a dynamic pipeline for acquiring them at dislocated prices; and Nigel’s thought process extends far beyond merger arbitrage—as we demonstrated in our Bitcoin Treasury Series.

Whether you're a merger arbitrage expert or beginner, and regardless of whether you plan to invest in special situations, you will find value in our new series Let’s Break A Deal—beginning with this inaugural installment—because we're applying these tools and frameworks through an entirely new lens.

This series is for all types of investors.

Twitter/X: @bewaterltd Website: bewaterltd.com

Not investment advice. For educational/informational purposes only. See Disclaimer.

Merger Markets As Multiflation Barometers

The merger arbitrage and event-driven universe serves as part of our early warning system for detecting shifts in Multiflationary forces. Even investors who never trade events should understand the process and monitor this universe for real-time intelligence on Multiflation’s direction and velocity, as well as market stress and complacency—before these signals manifest in broader credit or equity markets.

In Investing In The Age Of Multiflation (link here), we began charting a course to preserving and growing wealth in a Multiflationary environment. One of the defining features of Multiflation is dislocation; where there are dislocations there are investment opportunities.

Dislocations manifest in many forms—and we will discuss both those forms and specific dislocation opportunities in future essays—but here we focus on one specific subset of dislocations that repeatedly provides fertile hunting ground: mergers.

Every announced merger is—by definition—a potential dislocation waiting to happen. As we noted in The Factory That Makes Investment Processes Repeatable (link here), most merger arb situations follow a predictable pattern: deals eventually close on terms, but many deals also experience some sort of a hiccup before reaching completion.

Merger markets aggregate multiple data points—including regulatory sentiment, financing availability, management confidence, and strategic priorities—into observable price signals. When deals face unexpected regulatory hurdles, financing complications, or deteriorating fundamentals, these snags may represent the first visible signs of macro forces reshaping sectors or markets. Yet many investors miss these signals because they treat special situations and event-driven investing as entirely separate disciplines from macro and fundamental investing.

This separation may blind them to the linkages between why special situation events occur—or don't occur—and broader macro and sectoral developments that are taking place. For example, the 2007 financial crisis demonstrated the predictive power of merger arbitrage spreads when they widened ahead of broader credit market deterioration, which itself preceded the equity market collapse of 2008.

As we profiled in ‘CEF Activism At An Inflection Point’ (link here) we use a variety of tools to track Multiflationary forces. Widening spreads—including spreads across the closed end fund universe, merger arb, and credit markets more broadly—all tend to provide early tells that stress may be percolating under the surface. Conversely, when spreads compress to historically tight levels, they typically reflect abundant liquidity and aggressive risk-taking.

Understanding these patterns—and how Multiflation interacts with special situations—allows investors to position ahead of broader dislocations, whether they choose to trade the specific merger situations or simply use the intelligence to inform other investment decisions.

Practical Applications Within The Multiflation Portfolio

For those who do choose to invest in merger arb as part of the Multiflation Method, there are several ways to employ it as a tool within a Multiflation Portfolio. Most relevant for the majority of investors is that announced mergers may be used as a potential future shopping list—particularly when they overlap with Multiflation Archetypes—so that they can be prepared ahead of time to capitalize on dislocations in case of deal hiccups.

Deal breaks and stumbling blocks may create opportunities to acquire Multiflation-resilient businesses at dislocated prices, often with clear liquidity catalysts such as renewed bidding or alternative buyers.

Merger arb may also be used as a cash and income alternative within a Multiflation Treasury when spreads are attractive. Finally, when spreads are tight, at-risk mergers can be shorted and may even collectively act as a tail hedge to add Resiliency to the portfolio—for example in the face of another significant global credit shock.

Reverse Engineering Failure Modes

The issue spotting and scenario mapping methodology we'll explore in this series—anticipating how mergers and acquisitions can break before those scenarios materialize—is applicable beyond merger arb and has become a cornerstone of both our investment process and the Multiflation Method.

Reverse-engineering failure points is incredibly useful to identify structural vulnerabilities across different asset classes and investment scenarios. We refined these concepts from merger arb through bank and subprime “burn down analysis” during 2007-2008, and systematically mapped potential failure cascades before they materialized.

More recently, we applied this same method to research historical parallels between Bitcoin Treasury companies and the 1929 Crash scenarios (link here)—and to develop a customizable ChatGPT prompt (link here) that reverse engineers structural vulnerabilities in Digital Asset Treasuries.

Let’s Break A Deal: Alliance Data Systems

As with all of our stories, names and details have been changed to protect the privacy of those involved, including ourselves. The characters depicted are a blend of several of our mentors and colleagues.

Nigel unplugged the projector mid-sentence, and the tension in the boardroom escalated noticeably.

Until that moment, our merger team meeting to discuss Blackstone’s just-announced 2007 acquisition of Alliance Data Systems (ADS) for $8 billion had been unremarkable. Dave had the video projector running smoothly to ensure that no technical hiccups disturbed our discussion; Nigel despised ‘technical difficulties’. The merger documents were queued up, and Mo was walking through the deal with his usual methodical precision.

Nigel suddenly motioned me for a beer, cut off Mo’s walkthrough of deal mechanics, and began dismantling everything we thought we had understood about the deal. Within minutes, he had moved the whiteboard to center stage in front of the projector, and demanded printed copies of the merger agreement for everyone in the room.

"You're not wrong, but you are thinking about this far too narrowly," Nigel told Mo. "You’re also focusing on fake tells and noise—what people think matters, but is actually an intentional or unintentional red herring. The answer is obviously in the merger agreement, but you’ll never understand how much a buyer wants to close it versus escape just from the merger agreement document in isolation.

Nigel took a swig from his Coors bottle, and began probing deeper into the financing structure and Banc of America and Lehman’s involvement. “You have to read all of the documents in concert, and layer in incentives and human behavior, to find the real gaps in the interpretation of the Definitive Merger Agreement".

Nigel pressed deeper. "Now. Tell me again,” he said to the room. “How do you think they can weasel their way out of this deal?". Mo quickly offered the obvious answer: financing. “Wachovia is in trouble from subprime, they could refuse to fund, and the other banks would have to step up.”

"Sure," Nigel shot back, "they could also call up Lehman and First Boston and ask them to pull the staple, claim market conditions. But then they’re on the hook for some portion of the break fee and the banks have to pay the rest. Banks hate paying break fees—they'd rather just negotiate better deal terms."

Dave shifted uncomfortably as Nigel continued mapping scenarios. Blackstone could extend the marketing period, but that was just delaying the inevitable. If they really believed a recession was coming, they could try to walk away and fight it out in court, but that would destroy their reputation and future deal flow.

What followed was a masterclass in merger arbitrage due diligence, dark arts, and game theory. For the next four hours, Nigel systematically mapped out every conceivable way the Alliance Data transaction could break. He drew connections between the Termination language in the merger agreement, specific performance clauses, the background details contained within the proxy statement, and the redacted staple financing letters from the banks.

He had our team pull recent precedent transactions as well as other deals from his photographic memory of prior LBO deal waves—TXU, previous KKR deals, Bain transactions, Alltel—and began building a comprehensive framework of potential failure points for deals both with—and optically without—financing conditions.

“You can’t just read one passage in one part of the document and accept it at face value,” Nigel lectured us. “Instead you almost have to take sentences from three documents, slice them up, and then tape them back together, and then read that versus what was said in the source of truth, the Definitive Merger Agreement.”

“The other documents can change the interpretation of the merger document, or say something entirely different from the merger document. Just because a financing condition had been waived didn’t mean it was really waived. And just because there wasn’t a covenant in a deal with financing conditions, doesn’t mean it wasn’t in a document that was redacted, such as a staple financing.” All deals had embedded financing conditions; Nigel simply forced us to look more closely at the language and think through the implications more deeply.

By midnight the conference room had transformed into something resembling a detective's command center. Documents were organized in strategic piles with color-coded sticky notes marking contradictions and connections. Every inch of the whiteboard was plastered with merger agreement clauses, board member connections, and detailed analyses.

Mo rubbed his eyes. Dave had long since stopped taking notes. The rest of us sat transfixed as Nigel drew lines between seemingly unrelated pieces of information, revealing patterns invisible to mere humans. Finally, he stood before this maze of information, marker in hand, eyes gleaming with the intensity of someone who had just glimpsed the solution to a puzzle.

"So,” Nigel asked intently. “How do they get out of this deal without actually walking away from it?" Nigel clearly already had his answer.

Silence.

“Regulatory”, Nigel declared triumphantly “The key is regulatory. That's the elegant solution. No break fees, no reputation damage, no financing fights. Just point to regulatory concerns and let the government kill the deal for you.”

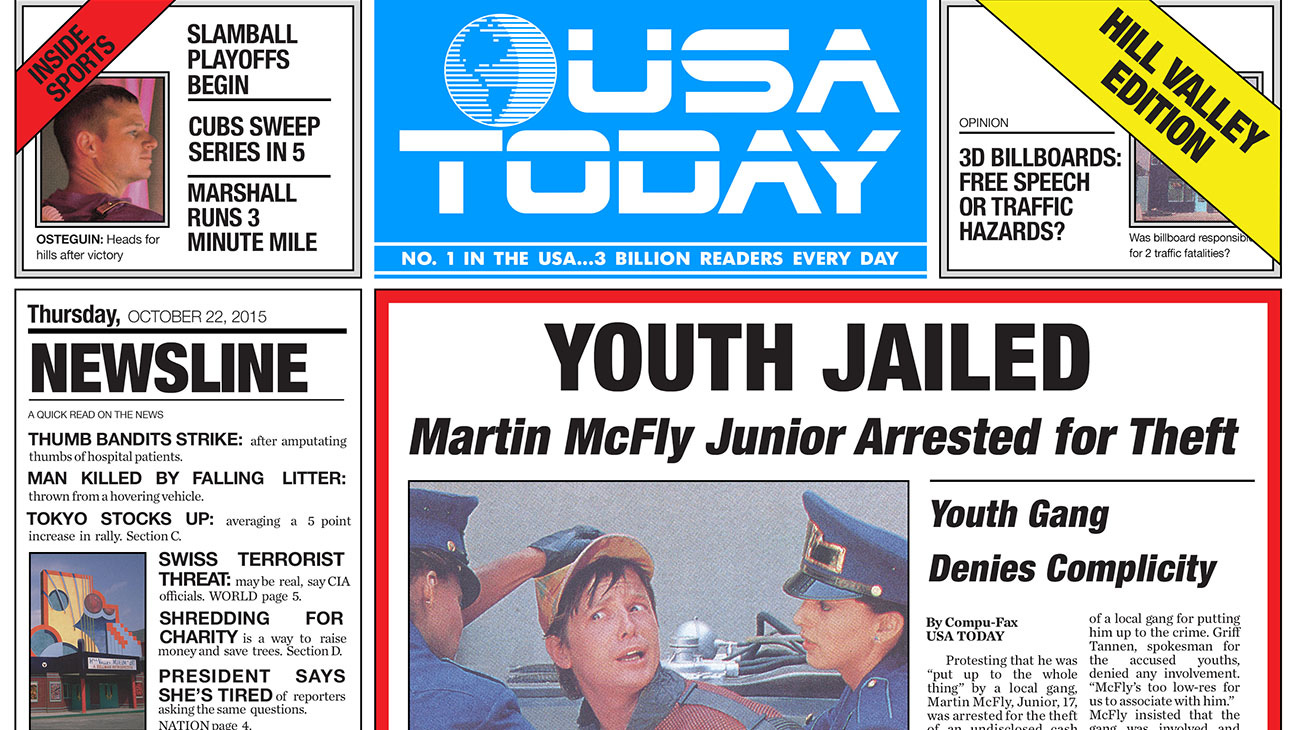

Nigel’s Process: Back To The Future

This was Nigel's signature approach: anticipating every possible headline—we call this issue spotting—that could break a deal before those headlines ever materialized. Like Marty McFly reading future USA Today headlines in Back to the Future, Nigel taught us to see potential market dislocations before they occurred. He understood that the real edge in merger arbitrage came not from legal or financial analysis alone, but from anticipating human behavior and market reactions to unexpected information.

Nigel’s process was methodical. First, identify everything that could go wrong. Second, trace those risks back to specific language in the merger agreement and other filings. Third, wait for the market to panic in the event that one of his anticipated scenarios materialized. He knew which earnings misses were carved out in merger agreements and which contained unique language that differentiated them from sector peers. He understood when to examine credit agreements for banking commitment levels and when proxy statements revealed the real story about executive incentives. Finally, he would deploy capital aggressively while others were selling in fear.

The ADS deep dive exemplified Nigel’s philosophy perfectly. When markets faced the inevitable volatility that followed, he was prepared for scenarios others hadn't considered. That night's lesson—and many others like it from Nigel and our other mentors—became foundational to our investment process and the Multiflation Method.

The integration of Let’s Break A Deal ideas within the Multiflation framework allows us to analyze, anticipate, and capitalize on on the structural dislocations that define our current economic environment.

Clearlake’s Dun & Broadstreet Bid: A Post Mortem

The Clearlake-Dun & Bradstreet deal ultimately closed successfully several weeks ago, joining the 95% of announced transactions that reach completion. But examining its potential pressure points retrospectively allows us to illustrate Nigel's methodology—how to identify and white board potential break scenarios even in deals that appear destined to close smoothly (and do in fact eventually close smoothly)—and explores how this tail risk could have become an issue.

The DNB merger agreement contained multiple structural vulnerabilities that—under different market conditions—could have created exactly the kind of dislocation that provides both trading opportunities and early intelligence about Multiflationary forces reshaping credit markets.

Marketing and syndication periods as outlined in merger agreements typically pose little risk when parties remain aligned in their desire to close the deal. But when fundamentals are deteriorating and leverage multiples are expanding, lenders sometimes balk at what they're being asked to fund—creating leverage for buyers to renegotiate or walk away entirely.

What made the DNB situation interesting was the velocity of its fundamental deterioration against a backdrop of extraordinarily tight credit spreads.

This created a potential opening for Clearlake. The marketing period language in the merger agreement—coupled with the pressure cooker end date approaching before Christmas—could have provided them with an opportunity to push back on the current deal price to extract a better transaction for themselves. They could potentially even have found a way to walk away entirely without paying the $266 million break fee.

This created a fascinating study in competing incentives. We know shareholders desperately wanted to close on current terms—they're mainly event-driven investors, merger arb players, and others trying to collect that last mile spread. Meanwhile, Clearlake faced the uncomfortable prospect of closing a deal that had become significantly more expensive than what they originally negotiated for due to DNB’s deteriorating fundamentals.

Then there was the incoming management team that would actually have to run this company on Clearlake's behalf. Do they really want to inherit a balance sheet and business fundamentals that are materially worse than when the deal was announced? Can they realistically execute a turnaround under these constraints when organic growth remains elusive?

Despite these mounting pressures, the deal still closed on existing terms. But the misaligned incentive structures created a genuine tail risk that could have resulted in a very different outcome. Incentive structures matter, and when push comes to shove, many parties and concentric incentive structures were involved here.

Note: If the DNB analysis seems overwhelming, don't worry. We'll teach these concepts alongside specific case studies as the series unfolds. Stay tuned for more Let’s Break A Deal live deal analyses and Nigel stories.

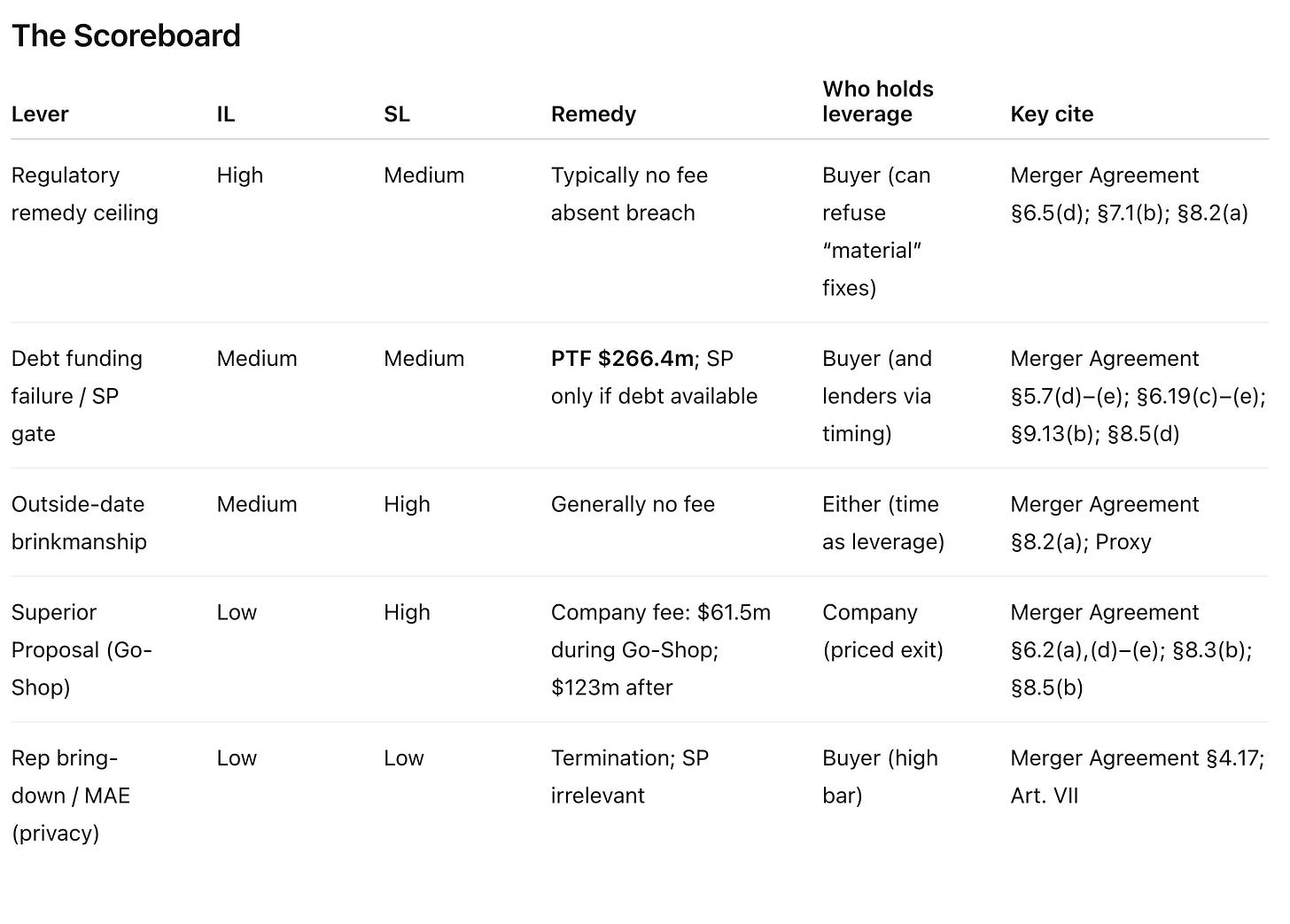

Appendix: How DNB × Clearlake Could Have Broken—in Three Moves

This deal can fail cleanly without anyone “breaching”: a regulator asks for too much, lenders take too long, or the calendar runs out.

The One-Minute Take

Dominant path: A built-in remedy ceiling lets the buyer refuse fixes that are “material to the Company,” so tough agency asks can stall past the outside date (Merger Agreement §6.5(d); §7.1(b); §8.2(a)).

What decides it: Whether required remedies cross that “material to the Company” line.

Outside date: Dec 23, 2025, auto-extends to Mar 23, 2026 if approvals alone are outstanding (Merger Agreement §8.2(a)).

Remedy posture: Parent Termination Fee $266.4m; Specific Performance of equity only if debt is available (Merger Agreement §8.5(d); §9.13(b)).

What could change: If regulators signal modest, non-core conditions and lender marketing wraps well before the outside date (Proxy; Merger Agreement §6.5(d); §9.13(b)).

What Made This Deal Fragile

1) The remedy ceiling is a hard stop.

The agreement forces “reasonable best efforts,” including divestitures or behavioral fixes, but it draws a bright line: the buyer doesn’t have to take any “Regulatory Action” that would be material to the Company. That’s a built-in right to say “no” if agencies push into core assets—then let the clock do the work (Merger Agreement §6.5(d); §7.1(b); §8.2(a)).

2) Specific performance is gated by debt.

You don’t get to court and force equity unless the debt is available at closing. The contract acknowledges maximum lender flex and bars adding new conditions—but if marketing isn’t done or debt isn’t there, equity SP is off the table. Practically, that makes the Parent Termination Fee the cleaner path if markets wobble (Merger Agreement §5.7(d)–(e); §6.19(c)–(e); §9.13(b); §8.5(d)).

3) The calendar is ticking time bomb.

Outside date is 12/23/25, with an auto-extension to 3/23/26 only if approvals remain. Closing may wait for the Marketing Period, which lives with lenders—not the target—so time can expire without a “breach” to litigate (Merger Agreement §8.2(a); Proxy).

Three Ways It Could Break

Move #1 — Regulator asks to carve the crown jewels

Trigger → Chain → Outcome:

A regulator demands a divestiture or restriction that crosses the contract’s “material to the Company” ceiling → the approval condition isn’t satisfied → the outside date (plus the limited extension) expires → the deal terminates, typically without a fee absent breach (Merger Agreement §6.5(d); §7.1(b); §8.2(a)).

“Parent and Merger Sub shall not be obligated… to take any Regulatory Action that would… be material to the Company…” (Merger Agreement §6.5(d))

Bottom line: If remedies hit that ceiling, the buyer can lawfully hold out and let the clock run.

Move #2 — Lenders take their time; SP can’t cross the bridge

Trigger → Chain → Outcome:

Debt marketing drags and/or lender flex bites → the Company can’t compel equity unless debt is available → buyer elects the Parent Termination Fee ($266.4m)rather than litigate specific performance → deal ends (Merger Agreement §9.13(b); §5.7(d)–(e); §6.19(c)–(e); §8.5(d)).

“Specific performance… only if the Debt Financing has been funded or will be funded at the Closing.” (Merger Agreement §9.13(b))

Bottom line: When financing is the bottleneck, the contract routes you toward the fee, not the court.

Move #3 — The clock quietly wins

Trigger → Chain → Outcome:

All other conditions line up, but the Marketing Period or last approvals slide into the outside-date window → extension runs out → termination, typically no fee absent breach (Merger Agreement §8.2(a); Proxy).

Bottom line: The agreement explicitly allows a timing break—even with good behavior on both sides.

Timeline to Watch

Outside date: Dec 23, 2025; auto-extend to Mar 23, 2026 if approvals are the only open item (Merger Agreement §8.2(a)).

Marketing Period: Closing may wait for lenders to finish marketing; this can defer closing without a breach (Proxy).

Payoff mechanics: Existing facilities paid at closing (can interact with timing) (Merger Agreement §6.17; §5.7(d)).

Material Adverse Event Sidebar

Delaware courts view an MAE as a durationally-significant adverse event that strikes at the very heart of the deal, creating a high burden of proof for the party invoking it (see, e.g., Akorn v. Fresenius).

Selected Clauses

“shall not be obligated… to take any Regulatory Action that would… be material to the Company” (Merger Agreement §6.5(d))

“Specific performance… only if the Debt Financing has been funded or will be funded” (Merger Agreement §9.13(b))

Outside date mechanics and auto-extension (Merger Agreement §8.2(a))

Parent Termination Fee $266.4m (Merger Agreement §8.5(d))

Go-Shop fee $61.5m; standard fee $123m (Merger Agreement §8.5(b))

Marketing can defer closing (Proxy)

This is probably the most incredible thing I have ever read on substack.

This is great, I actually passed on playing the Dun & Bradstreet deal and I feel better about that after reading this!