HyperPrices: When AI Rewrites The Invisible Hand

The Rise of SkyNet: The Algorithmization Of Finance Part II

New to the Sorcerer’s Apprentice series? Start with our foundational posts on Hyperreality and the Financial Matrix for essential context, or explore the full Table Of Contents.

Originally published privately on January 13, 2021. Updated, revised, and expanded for public release on October 10, 2024.

Note: This piece predated the AI revolution of 2022-2023. From the vantage point of late 2024, our exploration of algorithmic finance might initially appear quaint. However, the emergence of ChatGPT-3.5 and its successors has only amplified the relevance of these ideas in the interim. The questions we grappled with four years ago—probing the nature of modern prices, the autonomy of digital systems, and the future of finance—have only grown more pressing and complex. As AI relentlessly reshapes our world, the challenges to our understanding of markets, money, and reality itself have intensified exponentially.

In Skynet Part I, we embarked on a surreal odyssey through the algorithmic underworld, venturing into an imaginary Costco where “HyperPrices” flickered and fluctuated with manic intensity. These ephemeral numerical phantoms—untethered from reality and more akin to feverish hallucinations than meaningful economic signals—offered a glimpse into a world where the very concept of price had lost all meaning: “The problem with Costco HyperPrices isn’t that they are high or low, expensive or cheap—those concepts no longer apply. HyperPrices are just...abstract numbers floating freely in the ether.”

Costco HyperPrices aren’t merely a thought experiment, however—they increasingly mirror real-world phenomena as algorithms etch their digital footprints across the landscape of modern commerce. As they weave their sorcery—inexorably enmeshed with The Metamorphosis Of Money and the Keynesian Kaleidoscope—they are warping the fabric of finance and reshaping markets, if not society itself, in ways both subtle and profound. As we navigate the Financial Matrix, we’re forced to question the very foundations of our economic reality.

Ten Milestones On The Road To Hyperreality: Contents

1. The Metamorphosis Of Money

2. Keynes' Kaleidoscope

3. Central Banks’ Money Printer Go BRRRR

4. Silicon Shadows

5. The Rise of Skynet <== YOU ARE HERE

6. The Institutionalization Of Finance

7. The Symbolic Alchemy Of Risk

8. “We’re All Quants Now”

9. Social Media & “The Ecstasy Of Communication”

10. The Consumerification of FinanceHyperPrice Melt-Ups And Melt-Downs

Algorithmic pricing systems have become ubiquitous in e-commerce. These digital black boxes decide what they “think” a product should cost, and—without human input or oversight—iteratively steer the price up or down based on certain formulaic criteria.

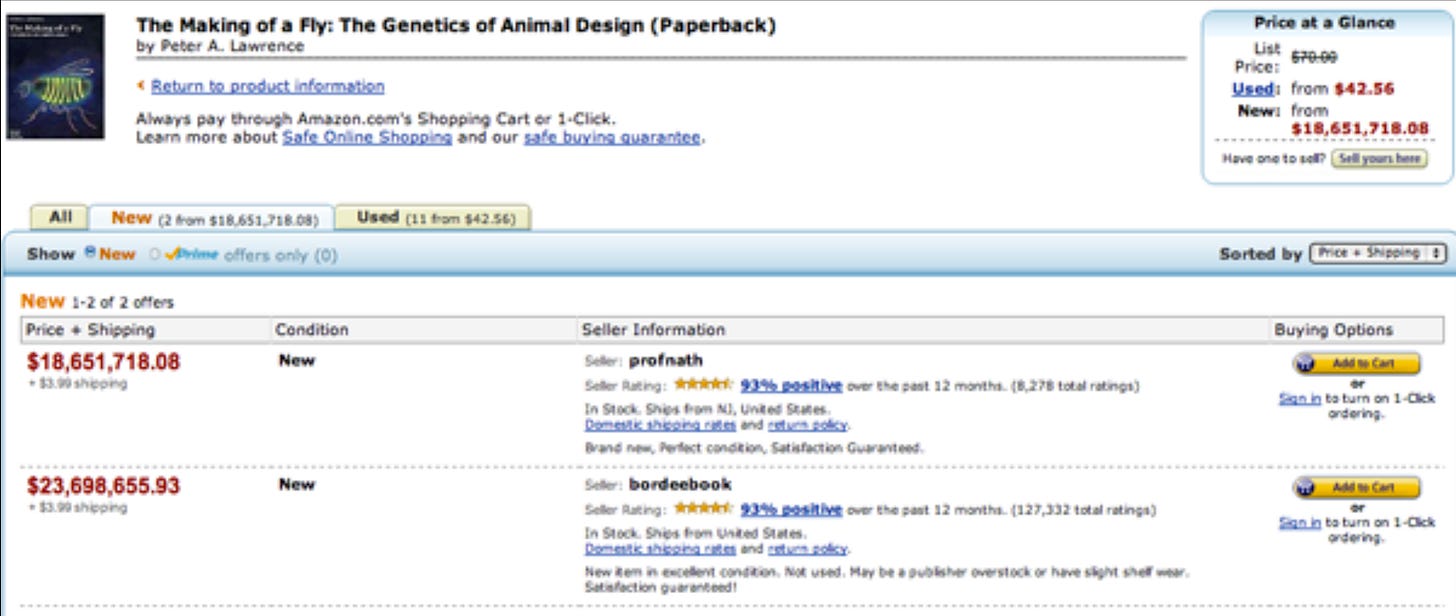

In 2011, two algorithms on Amazon famously became caught in an adversarial feedback loop, driving the price of a book about housefly genetics—normally priced at ~$15—up to an astronomical ~$24 million:

Fortunately, this hyperreal algorithmic skirmish concluded without an actual sale, rendering the incident more comedic than concerning. Nonetheless, it looms as a stark harbinger that real-world algorithms—just as in our imaginary Costco scenario—can, even without buggy code, conjure wholly fictitious price points from the digital ether.

These HyperPrices—untethered from the real world of supply and demand—exist in a realm of pure digital abstraction. Consider the implications: if algorithms can autonomously spawn such extreme pricing anomalies, can we truly place our faith in the ostensibly “normal” prices we encounter in the digital bazaar—or even in the brick-and-mortar world? And what of the asset prices that flicker across our Bloomberg terminals and Robinhood apps?

While the fly book incident resolved harmlessly, its portentous nature went unheeded. Three years later, a comparable glitch in the Matrix created the e-commerce equivalent of a flash crash. Our Sorcerer’s brooms sent prices plummeting and unleashed genuine chaos—a chilling reminder of our virtual code’s latent power to sow real-world pandemonium.

For around an hour, RepricerExpress—an automated pricing system utilized by Amazon MarketPlace sellers—slashed the prices of thousands of items to a mere penny. Orders were swiftly processed by Amazon's automated warehouses, leaving vendors powerless to intervene or cancel the transactions.

HyperPrices: Glitches In The Matrix, Not Bugs

It’s crucial to emphasize that programming errors are not our concern here. Throughout financial history, markets have always contended with errors like “fat finger” trades, miscalculations, and other mishaps. These isolated incidents—while occasionally highly disruptive—are fundamentally different in nature than the systemic issues we’re now experiencing due to the pervasive use of algorithms in price determination.

Our inquiry is concerned with a far more profound phenomenon: the genesis of hyperreality and HyperPrices. The digital revolution catalyzed a fundamental transformation in how prices are determined—a change that appears to be partially an emergent property of the complex interactions between algorithms.

The challenge we face, therefore, is not simply one of debugging code or fixing isolated errors. Rather, we are grappling with glitches in the Financial Matrix—where HyperPrices occur as abstract numerical phantoms divorced from the real world.

Project Nessie: Clandestine Project To Levitate Prices

So far, we’ve primarily focused on emergent behavior of algorithms leading to extreme HyperPrices. However, as we explore the algorithmic underpinnings of modern markets, we soon encounter a more subtle and deliberate form of HyperPrices. This involves the purposeful design and deployment of algorithms to steer prices and market dynamics—granting their creators advantages that were simply unattainable prior to digitization:

A Wall Street Journal exposé revealed that Amazon deployed a secret algorithm—known as “Project Nessie”—that would allegedly increase prices and monitor competitors, such as Target, to see if they followed suit. If competitors did not raise their prices, Amazon would revert to the original price. This allowed Amazon to maximize profits by testing how much it could raise prices without losing competitiveness, resulting in higher prices across the board—including at retailers with brick-and-mortar locations, who frequently match their online pricing to physical shelves.

Matrix Relobbied: Agent Smith Hacks The Hill

Now, in a free market under a sound monetary system, we would disagree with the FTC’s characterization—there is nothing inherently wrong with what essentially amounts to a public auction to assist price discovery and profit maximization; at the end of the day consumers are the captains of the economic ship. They are generally sovereign and can vote with their dollars; Amazon cannot force consumers to pay more for an item than it is worth to them.

But our present circumstances are considerably more complex. First—and perhaps most importantly—as we showed in the Metamorphosis of Money and Money Printer Go BRRR, we do not operate under a sound monetary system. Second—as detailed in the Keynesian Kaleidoscope—our economic system has, particularly since 2008, increasingly diverged from what would traditionally be considered a free market.

Government fiscal and monetary interventions fundamentally alter pricing dynamics, directly and indirectly impacting algorithmic pricing strategies such as Nessie. In an environment of expansionary monetary policy and extensive government interventions, the notion of consumer sovereignty erodes, yielding to government sovereignty and Cantillon effects.

When a government or central bank borrows or prints money to buy a good or service—as is effectively happening under a welfare state, even when a nominal “consumer” executes the transaction—the “price” paid is not a true market price. Rather, it is an Olympian expression of desire detached from economic reality and devoid of true economic constraints.

Recent Covid PPP and EBT scandals exemplify this phenomenon. These initiatives allowed recipients to spend government funds, introducing significant artificial demand disconnected from individual economic productivity, authentic consumer preferences, and financial constraints. Consumers armed with this artificial purchasing power can increasingly become the marginal price setters across various markets. (This crucial concept will be explored in greater detail in later installments and holds equal significance in asset markets—for instance, as the Bank of Japan becomes the largest owner of equities.)

The “vendor financing” cycle of recent decades further complicates matters: the U.S. government borrows or prints currency, which it deploys to subsidize algorithmically-priced purchases by consumers—often for goods manufactured in countries like China. These manufacturing countries, in turn, recycled their trade surpluses by lending money back to the U.S. government, thus perpetuating and intensifying this financial feedback loop.

In conclusion, it’s entirely likely that—in many instances—advanced AI algorithms are becoming extremely adept not at discovering and optimizing for “what the [real] market will bear”, but rather for exploiting what the government and central bank are willing to (indirectly) pay. Worse yet—as these algorithms relentlessly maximize prices and profitability—the government may find itself compelled to escalate subsidies repeatedly, perpetuating a cycle where AI systems swiftly adapt to exploit each new financial intervention, contributing to HyperPrices that are increasingly detached from economic “reality”.

RealPage & Algorithmic Rent Inflation

Similar issues crop up virtually everywhere algorithms are deployed to help determine prices. RealPage—a large property management software company—has come under DOJ scrutiny for its use of AI-driven pricing algorithms in the rental housing market.

Again, in principle, we have no objection to algorithms facilitating price discovery and profit maximization. However, rather than operating within a free market based on straightforward expressions of supply and demand, RealPage’s algorithms instead operate within a complex matrix of monetary policies and government interventions—and create a layer of hyperreal rental prices in the process.

For example, even if we focus solely on recent subsidies related to rental housing for “undocumented” immigrants, it seems likely that algorithms such as those used by RealPage may be “optimizing” for government-induced purchasing power—as it simultaneously collides with other government policies that artificially constrain housing supply—rather than true consumer demand constrained by individuals’ personal financial situations. Consider these examples:

New York spent $1.98 billion solely on housing and rent

Massachusetts spent nearly $1 billion in a year

The result is that non-subsidized citizens may no longer represent the marginal buyers or price setters in the rental market.

If the government is willing to pay above market prices, it could even make sense for a profit-maximizing algorithm to evict non-subsidized citizens or let vacancies increase, further decreasing availability and affordability for non-subsidized renters. Indeed: “but when [RealPage] began using YieldStar, managers saw that raising rents and leaving some apartments vacant made more money”. Non-subsidized renters are left struggling, contributing to the oft-discussed "rental crisis":

This dynamic creates a feedback loop that may put persistent upward pressure on rental prices: as algorithms drive up rents to match government subsidies, the government may feel pressured to increase those subsidies further, which the algorithms will then exploit again.

Subprime Attention Crisis: AdTech Algos

While e-commerce platforms like Amazon grapple with the unintended—and sometimes intended—consequences of their pricing algorithms, similar challenges are emerging in other cornerstones of the digital economy such as online advertising. Here too, we see algorithms creating a layer of hyperreality through a combination of emergent algorithmic behavior and potentially deliberate programming.

Uber recently realized that it had been flushing $100million—or two thirds (!!!)—of its ad budget down the toilet on what were effectively “subprime advertisements”:

More recently, advertisers sued Meta over similar claims:

Now, in the above Uber and Meta examples, we can’t attribute all of the issues to hyperreal algo-on-algo skirmishes. But in 2023 and 2024, Meta algos did go wild and generate HyperPrices:

These sorts of AdTech issues were chronicled in Subprime Attention Crisis: Advertising and the Time Bomb At The Heart Of The Internet:

From the unreliability of advertising numbers and the unregulated automation of advertising bidding wars…Hwang demonstrates that while consumers' attention has never been more prized, the true value of that attention itself—much like subprime mortgages—is wildly misrepresented.

The book’s core thesis is that tech and advertising companies have financialized and bundled tiny slivers (similar to tranches) of “human attention” into discrete, liquid assets that can then be bought and sold in the global market. Algos are then used to trade advertisements as a commodity through real-time, high-speed techniques. Effectively, AdTech is a conceptual hybrid between subprime Mortgage Backed Securities (without the leverage), stock market High Frequency Trading algorithms, and the types of algos that artificially inflated the price of the fly genetics book on Amazon.

Because the algorithms are black boxes, the marketers who buy the ads cannot directly observe what’s actually taking place within their ad campaigns. This opacity encourages behavior that—as Uber and Meta advertisers discovered to their chagrin—potentially allows AdTech algorithmic platforms to wildly over-inflate the value of ad placements, alchemically transmute “subprime” ad placements into AAA-rated gold, or make the value up entirely (known as “attribution fraud”).

Paralleling the RealPage example above, AdTech algorithms likely also converged with government interventions—in this case, the influx of cheap capital from Quantitative Easing (QE) policies—to amplify HyperPrices. As the “QE Subsidy”—a form of corporate welfare—fueled investment in the tech industry, many companies spent lavishly on digital advertising. AdTech algorithms, in turn, presumably swiftly adapted to extract maximum value from these artificially inflated budgets.

Conclusion

The tendrils of algorithmic pricing have infiltrated virtually every corner of our economy—from e-commerce to online advertising to real estate—and are increasingly warping the fabric of the price system. HyperPrices are not merely bugs, but rather emergent—and sometimes deliberately engineered—properties of our increasingly algorithmic world that arise from the complex interplay between competing algorithms, government policies, and central bank interventions.

Up Next:

While we may laugh at the $24 million fly genetics book, and few may shed tears over advertisers being overcharged, algorithms exhibit similar behavior in other scenarios where the stakes are considerably higher—directly impacting our own investment portfolios and the global economy.

In Part III we'll explore how algorithms are reshaping the foundations of our financial markets within the Financial Matrix.