The Synthetic High That Became Its Own Reality

Wall Street's Casino: The House Always Wins—And Now It's Rewriting Reality

Markets exist to coordinate human action in accordance with reality. Instead, they’ve increasingly come to replace reality.

The ETF wrapper has usurped its contents. The derivative matters more than the underlying. Derivatives move wrappers that move underlying stocks, which spawn narratives amplified by social media and AI, which generate additional trades by humans and machines. The tail is wagging the dog—financial markets have morphed into surreal, nested layers of abstraction that feed on one another in a closed, self-referential loop.

The companies exist somewhere underneath, of course, but the market—and capital flows—are now governed by representations rather than reality, by shadows rather than substance.

Welcome to the Financial Matrix: a hyperreactive simulation of markets dominated by vibes, memes, ETFs, AI, and machine logic. We’ve been documenting this transformation in our long-form series The Sorcerer’s Apprentice & The Man Who Broke The Market.

Twitter/X: @bewaterltd | Mojo Website: bewaterltd.com

Not investment advice. For educational/informational purposes only. See Disclaimer.

Inside The Grow House: From Seed to…What, Exactly?

Of all the places to glimpse the Matrix’s code laid bare, a $600 million cannabis ETF seems an unlikely candidate. AdvisorShares Pure US Cannabis ETF (MSOS) isn’t particularly noteworthy in and of itself—cannabis is a trivial corner of the economy and MSOS is a rounding error within the ETF universe.

To the casual observer, MSOS appears to be the simplest and cleanest way for wealth managers and retail investors to bet on U.S. marijuana reform, or at the very least to gauge how others are betting. As the largest cannabis ETF to survive the COVID-era ‘weed bubble’—one facet of the all-encompassing market mania documented in Mr. Market’s Schizophrenic Break—MSOS has become the definitive scoreboard for the cannabis industry.

Millions of shares change hands every day. It has a full options chain. It boasts pages of “institutional holders” on Bloomberg. MSOS is the “easy button” for trading cannabis: why research dozens of operators scattered across obscure Canadian exchanges, navigate state-by-state regulations, and decipher an industry operating in legal limbo when you could simply buy the ticker imprinted with “U.S. marijuana” on the label?

The problem is that the scoreboard is so broken that we no longer even know what game we are playing—and what’s true for MSOS is increasingly true for the financial system itself.

MSOS is simply one corner of the markets in which the scrolling neon green code animating the Financial Matrix becomes legible. As with Volmageddon, the simulation only reveals its true nature when you zoom in closely enough to see the glitches. Once you spot the pattern in truly dysfunctional markets like MSOS, you’ll recognize the same fractal repeating throughout the Matrix—even in seemingly functional markets operating at trillion-dollar scales.

Reefer Madness

There’s something deeply wrong with MSOS. Not wrong in the “ETF is badly managed” sense or the “temporary underperformance” sense, and not even in the “weed is uninvestable” sense.

MSOS is a simulation of exposure to “cannabis” that has become the primary reality market participants respond to—the type of financial hyperreality that we’ve been writing about in the Sorcerer’s Apprentice. When MSOS rallies, the narrative becomes that “cannabis is back”. When it sells off, “the sector is dead.”

All participants in weed stocks—retail traders, trading algorithms, dealers, promoters, media—now react to the price of MSOS itself, which moves the underlying stocks, which validates the reaction to MSOS as “fundamentally true”.

A Simulation That Has Become Real

Yet few investors and observers understand how inverted the MSOS “reality” really is. For starters, it doesn’t even own stocks in the companies whose performance it allegedly measures. In fact, it cannot—U.S. law prohibits conventional ETFs such as MSOS from directly holding plant-touching cannabis operators because these firms remain illegal at the federal level. Indeed, that’s precisely why the ETF exists in the first place.

So instead, MSOS owns something else entirely: indirect IOUs on cannabis stocks. And the managers of MSOS actively trade these synthetic positions like a hedge fund rather than passively tracking a known basket or index. Its performance therefore reflects the fund manager’s own trading decisions as much as the industry performance itself. The investor who thinks they’ve bought a simple index fund has unknowingly handed their capital to an active manager making discretionary swap trades, while dealers and intermediaries scalp the flows and extract fees at every layer.

If you peruse the MSOS holdings list, you won’t find “Green Thumb” and “Curaleaf,” but rather “Green Thumb Swap,” “Curaleaf Swap,” “Derivatives Collateral – Dealer X.” MSOS owns a stack of paper promises from counterparties who are running their own (likely hedged) book against the same names. It posts collateral, and in exchange receives the economic performance of a basket of cannabis names (after subtracting out hefty fees). The banks hedge their exposure as they see fit, often by trading the same names in Canada and OTC markets.

What started as a workaround for regulatory restrictions has metastasized into one of the most dysfunctional trading ecosystems in the Financial Matrix. The swap structure that regulatory constraints force upon MSOS makes it a better vehicle for quants and dealer trading books than patient capital. That dealer dominance warps the trading patterns—premiums, discounts, short interest, volume. Social media and retail interpret the chaos as manipulation or hidden signals, generating narratives that feed back into flows. And the volatility itself becomes the product, attracting promoters who extract value while amplifying the circus.

MSOS is a microcosm of a broader pattern in the Matrix: wrapper products that morph into scoreboards more real than the underlying game, in which social media narratives and trading flows matter more than the actual companies’ fundamentals (such as they are). Like the Bitcoin Treasury Companies, the MSOS ecosystem benefits everyone in the value chain—dealers, brokers, promoters, intermediaries—except for the investors who actually own it.

Social Media Circus

What makes MSOS particularly fascinating is how tightly the social media feed, the ETF tape, and trading algorithms have become intertwined, much as we discussed in Enter The Financial Matrix. Dealers move prices in response to flows and hedges. The social media and algorithmic feed interprets every move as a storyline—shorts attacking, reform coming, insiders buying, manipulation, whatever. Retail and trading algos pile in or bail out based on that narrative, which feeds back into flows, which feeds back into dealer behavior, which creates new narratives.

The managers of MSOS benefit from fees when assets under management explode during these rallies. Indeed, nearly everyone profits from the volatility itself, in both directions, regardless of whether cannabis reform—or any fundamental improvement, for that matter—ever actually happens. The only people who don’t profit from this circus are the retail “bag holders” getting churned by fees and long the ETF and stocks when the music stops.

Every few months, another newsletter author or influencer hypes an imminent “cannabis reform trade” to their followers or that they are seeing “massive inflows” into MSOS. Money piles in, the stock moves, and the promoter (allegedly) exits—using retail as exit liquidity—while continuing to post bullish takes. Then radio silence, until another “my sources tell me” setup begins.

It’s penny stock promotion 101—a playbook that dates back at least to the South Sea and Mississippi Bubbles, now relocated from Exchange Alley to Twitter and supercharged by algorithms that amplify every move. Reporters and social media amplify every rumor because it drives traffic. Lawyers and policy experts position as neutral referees while talking their books. Influencers trying to “unite the community” create drama for engagement.

Despite what retail investors think, the dealers running swap books and arbitraging premiums aren’t the true villains here—they’re providing liquidity for a broken structure created by the intersection of regulatory constraints and retail’s own FOMO/YOLO greed. The intermediaries’ incentives are transparent: extract fees, manage risk, facilitate trades. The bad actors tend to be the ones pretending to be on retail’s side while operating with completely opposing incentives—for example, “community leaders” who position themselves as selflessly guiding newcomers through the space.

Retail Red Herrings: “Institutional Owners”

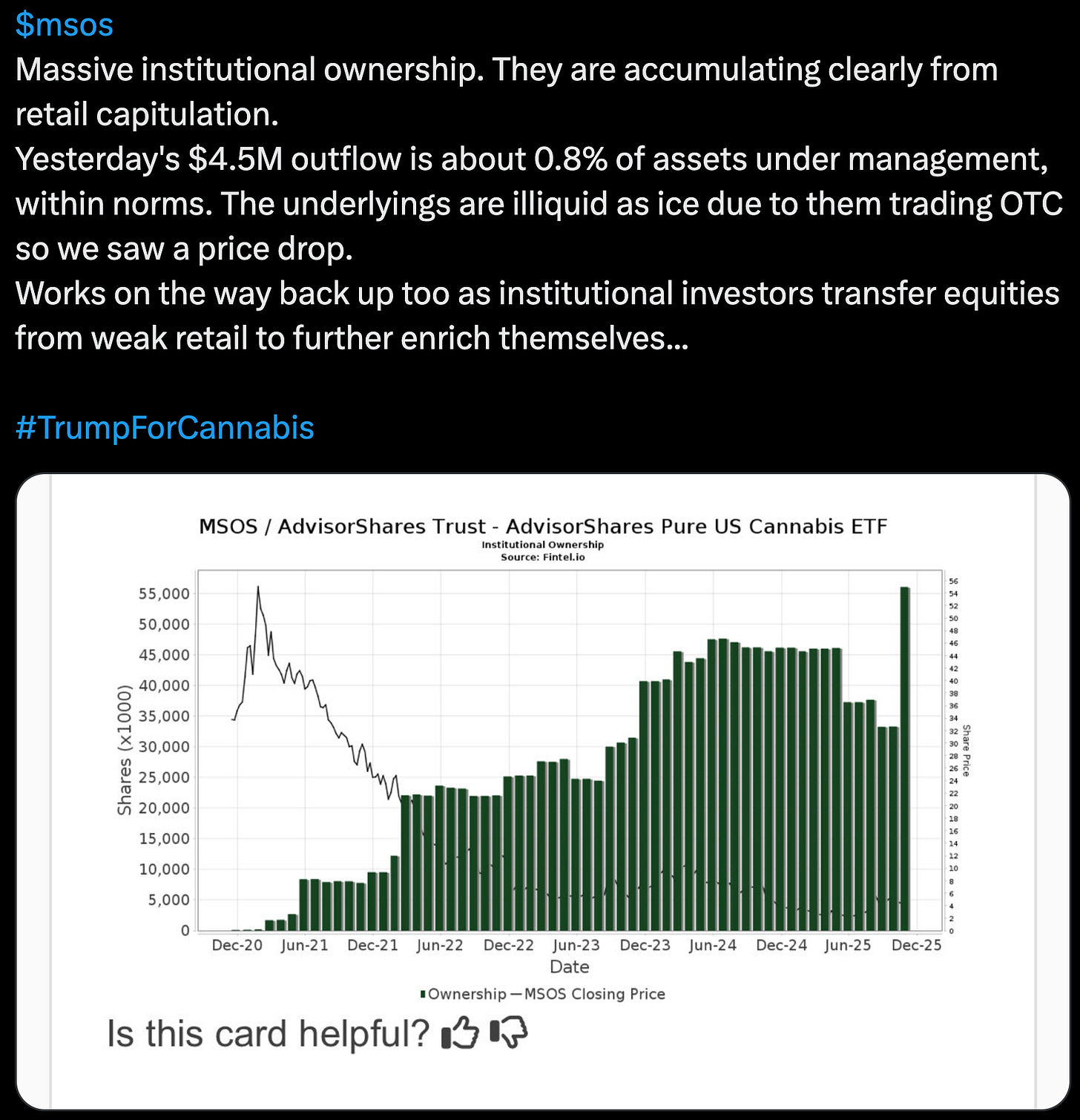

Retail investors—and even some professionals—scroll through the MSOS holders list and see validation: real money, serious allocators, patient capital. The reality is almost the opposite: what appears to be ‘ownership’ is actually ‘inventory.’

A grocery store holds thousands of apples, but they aren’t ‘long apples’—they are warehousing them for turnover. Similarly, by our rough estimates, up to three-quarters of MSOS float sits with dealers, brokers, market-making desks, and authorized participants warehousing creation units and running inventory.

MSOS ‘institutional ownership’ is predominantly just professionals managing their own risk. They’re long it here, short it there, long calls, short puts, short the ETF against a custom basket, leaning short to arb a premium or leaning long to cover a discount—the visible positions are just stale fragments of hedged, multidimensional strategies, similar conceptually to what we discussed in our recent piece on the 12D Chess of 13Fs.

The remaining quarter of the MSOS float, give or take, represents the “real” investor base: a handful of small funds and advisors with mandates flexible enough to tolerate “federally illegal” exposure—often with strict position limits and requiring offsetting hedges—plus retail investors and wealth managers who use MSOS because there isn’t a better alternative.

In short, few—if any—of the institutional holders are providing patient long-term capital with a positive disposition to industry fundamentals; rather, they generally see MSOS as just another token to be passed around, hedged, and arbitraged.

The trading patterns confirm this interpretation. On a typical day, MSOS trades multiples of the combined volume of several of its largest underlying holdings. The options market amplifies this further—tens of thousands of contracts flipping back and forth, creating millions of shares of synthetic exposure layered above the ETF’s base.

Then there are the satellite ETFs orbiting the same universe: MSOX, essentially a leveraged version of MSOS that amplifies its volatility and forces more hedging activity back into the underlying names; YOLO and TOKE, which add global cannabis exposure but still channel flows into the same small pond of operators and swaps.

Each additional wrapper and derivative multiplies the amount of synthetic flow hammering a very limited number of actual companies. The result is an ecosystem where the wrappers and their derivatives have become more meaningful than the underlying businesses they indirectly own. Yet the price of MSOS has become the authoritative signal that everyone watches to “see how cannabis is doing”: retail traders, cannabis podcasters, newsletter writers, even institutional allocators treat the ETF’s movements as the primary reality.

Retail Red Herrings: The Phantom Menace

The chaos in MSOS trading patterns generates endless speculation among retail investors, but what looks like conspiracy is usually just the mechanical reality of how swap-based ETFs actually function.

When retail sees MSOS trading at a premium to its net asset value, they interpret it as bullish demand or “smart money” positioning. When it trades at a discount, they see capitulation or dealer games. In reality, premiums and discounts in MSOS behave nothing like those in normal equity ETFs.

In SPY, arbitrage mechanisms keep premiums and discounts microscopic—authorized participants simply create or redeem shares against the underlying basket until any gap disappears. But MSOS can’t do that because its basket is mostly swaps, not actual shares. So premiums and discounts swing wildly based on dealer risk appetite, hedging flows, and the cost of maintaining synthetic exposure. These aren’t esoteric signals about the future of cannabis reform, but rather signals about the internal plumbing of the ETF structure itself.

The same confusion surrounds short interest. Retail investors see high reported short interest in MSOS and conclude that “shorts are attacking” or that a squeeze is imminent. But most of that short interest is almost certainly dealers hedging their own exposure—shorting the ETF to arbitrage a premium, hedging sold call options, or running relative-value trades between MSOS and other cannabis products.

There’s no cartoon villain or “Sith Lord” naked shorting or paying punitive borrow costs to crush retail dreams. There are, however, sophisticated counterparties with access to swap desks, internal inventory, and synthetic shorting mechanisms that don’t require the usual friction of stock borrow or the uptick rule. What retail interprets as coordinated manipulation is mostly just professionals playing an entirely different game with different objectives and tools available to them.

Conclusion: A Scoreboard Untethered From The Game

MSOS is a casino—a derivatives structure built primarily for the benefit of intermediaries—where the scoreboard has become disconnected from, and yet directly influences, the underlying reality it supposedly represents. We barely remember what game we were supposed to be playing in the first place—reality is whatever the last trade and the last Tweet said it was.

The toxicity of the marijuana space—rivaled only by crypto, and attracting the same breed of degen speculators—is hardly an accident. It is the inevitable result of mixing drug culture with gambling mechanics. The MSOS structure is a perfect trap: the seductive story of “inevitable legalization” hooks the believers, while the friction of transaction costs and fees bleeds them dry.

None of this makes it impossible to profitably trade the marijuana space. It does mean, however, that retail investors in particular need to understand the real game that is being played, not the one advertised on the label. You’re not investing in cannabis. You’re speculating on an actively-traded, swap-based wrapper designed to enrich intermediaries and leave you holding the bag. MSOS is a trading sardine, not an eating sardine.

But MSOS isn’t merely a cautionary tale about a broken weed ETF. The uncomfortable red pill is that MSOS is hardly an outlier. The same code is running everywhere in the markets, and the same fractal pattern recurs throughout the Financial Matrix. We see it in Bitcoin Treasury Companies, volatility products, meme stocks—even plain vanilla equity and bond ETFs—all exhibit variations of this Alchemy of Risk.

The Financial Matrix seems real only because you haven’t fully unplugged yet, and because the simulation perpetuates itself until reality forces a reconciliation. For MSOS, the only likely scenario that can break the spell is Federal reform, which would allow plain vanilla ETFs to own the stocks instead of swaps.

For the broader market, however, a crisis will likely be required to force the simulation to reconcile with reality, for example when everyone tries to redeem their paper IOUs at once and discovers how many layers of abstraction separate them from reality.

In the meantime, remember: you’re not in the market—you’re in the Matrix. And the Multiflation Method decodes how to navigate this treacherous investment environment.

Assuming everyone doesn’t liquidate SPY at the same time how much of this is really a problem for the large equity and bond ETFs?